When acquiring a new behavior, learners need ample opportunities to practice their skill. To develop their skill efficiently, learners need feedback. Therefore, when it comes to learning cybersecurity actions, feedback nudges are an effective instructional method because they provide learners with a vehicle for getting feedback on their cybersecurity actions. However—and this cannot be stressed enough—there are severe limitations on what can be accomplished in the few minutes a nudge is displayed.

In this blog post, we’ll show that nudges are a necessary component of a robust human risk management (HRM) approach to behavioral change. However, they must complement a broader educational strategy that includes other forms of instruction, including didactic and interactive learning experiences.

Nudges often rely on foundational knowledge: an example

Cognitive science has shown that people use different learning strategies and store knowledge in different forms (Chi & Wylie, 2014). Educators use specific teaching strategies to encourage thinking that helps learners build new knowledge or reshape what they already know (Nokes, Hausmann, VanLehn, & Gershman, 2011). So, if we know what kind of learning we want to achieve, how do we choose the best teaching method (Koedinger, Corbett, & Perfetti, 2012)?

To answer this question, and to make this a little more concrete, let’s start with a simple example. Suppose you were asked to solve the following multicolumn math problem:

Assuming you don’t have the solution memorized, you are going to calculate the sum by recalling a mathematical process you learned years ago. The first step is to ignore all the numbers on the left and focus on the right-most column.

You write down “5” in underneath that column, and you move your attention to the adjacent column. But here’s where you slip and make a mistake. As you write “2” (because 1 + 3 + 8 = 12), a tutor (either computer or human) notices your mistake and interjects by saying, “Don’t forget that you carried a one.”

This tutorial message is an example of a just-in-time hint (or a “JIT” for short; Corbett & Anderson, 1990) or a feedback nudge (Thaler & Sunstein, 2021; p. 118). The purpose of a JIT is to remind the problem solver about a step they may have inadvertently forgotten to apply (in this case, carrying a one).

The above feedback nudge is doing a tremendous amount of work because it assumes the individual understands the concept of place value and what numbers within those place values represent. There is a lot to unpack in that very short statement, and it requires the learner to have a conceptual understanding of addition for the message to make any sense.

In other words, this feedback nudge only helps if you have foundational knowledge of math (addition, specifically) stored in your long-term memory.

What is the impact of a JIT on learning?

As with most things in life, the answer is, “it depends.” In this case, it depends on the background knowledge of the learner. Evidence for the interaction between prior knowledge and the educational impact of a JIT can be found in the following observational study (Hausmann, Vuong, Towle, Fraundorf, Murray, & Connelly, 2013).

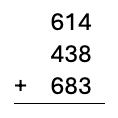

In their study, researchers tested two versions of a math tutoring program. One version gave students helpful hints (JIT messages) when they made common mistakes, like forgetting that a slope of a function is negative. The other version didn’t offer these hints. Students were also grouped by how much math knowledge they already had—either high or low.

Surprisingly, students with more background knowledge learned faster with the hints, while those with less knowledge needed more help when hints were included (see Figure 1). This suggests that hints are only useful if students already understand enough to make sense of them.

Figure 1. The interaction between prior knowledge (PK) and the availability of a just-in-time (JIT) instructional hint.

Phishing schema: a mental representation

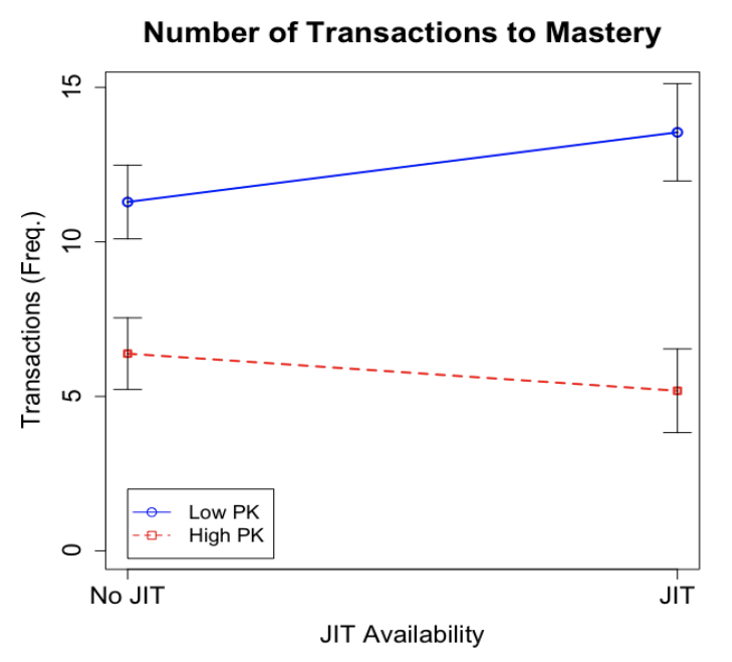

Given the importance of background knowledge, let’s turn our attention to one of the many representations the mind uses to organize and store the large amounts of information we encounter. One of the representations is called a schema, which you can envision as a series of slots that hold various values. An example of an extremely sparse schema might look like Figure 2.

Figure 2. A sparsely detailed schema for two topics: 1) reporting a phish, and 2) data loss prevention.

In the above schema, two cybersecurity topics are represented:

- The left side of Figure 2 shows the knowledge that’s required to detect and report a phish.

- The right side shows how the mid-level classification (concepts; detection; consequences; reporting) applies to another cybersecurity topic—in this case, data-loss prevention.

At the highest level of description, each topic can be described by four slots: concepts, detection, consequences, and reporting. The values for those slots, obviously, depend on the topic. The main point, however, is that at a high level of description, there is a common set of concepts that need to be acquired for each cybersecurity topic.

To adequately instruct someone about identifying and reporting a phishing threat, the minimum information we would need to cover is depicted on the left side of Figure 2. It is fair to say that this amount of information would not reasonably fit into a nudge. (Here, we will use nudges to refer to cybersecurity messages and JITs for educational contexts.) That would be equivalent to trying to teach multicolumn addition in a single JIT message.

Instead, what we can do with a nudge is to remind the learner about a lesson they encountered in a more formal instructional setting—for example, a training video or a phishing “how-to” guide.

What does this mean for cybersecurity?

There are a few implications for applying the practical limitations of JITs to nudges in cybersecurity education.

The first implication is that nudges alone will not save cybersecurity (Hausmann, 2024). They are too terse to adequately convey all the information that’s necessary to detect and report a potential security event. Instead, nudges should be viewed as a mechanism for providing learners with feedback on their actions.

Second, we know from the study cited above that the impact of a feedback nudge is going to depend on an individual’s background knowledge of the subject matter. This finding is consistent with Shute, 2008 (p. 180). As educators, we need to provide our learners with the foundational knowledge so that nudges make sense when displayed in context.

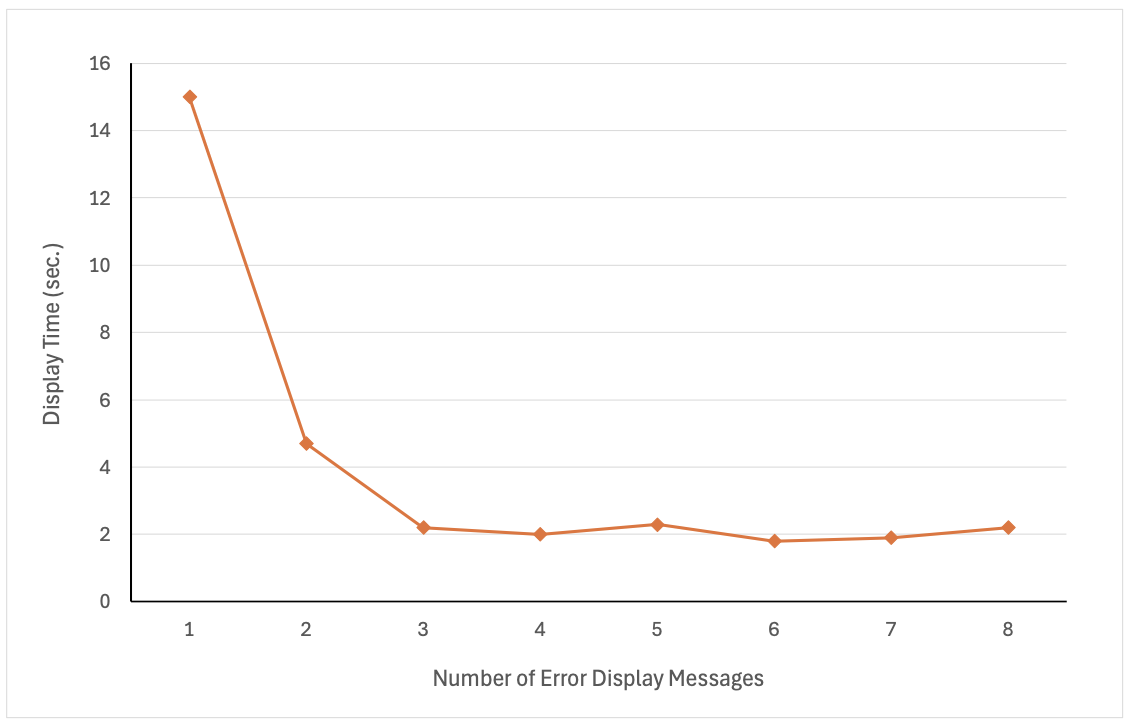

The original definition of a nudge is that it, “must be easy and cheap to avoid.” (Thaler & Sunstein, 2021; p. 8). Easily dismissed items tend to be ignored. In addition, we tend to habituate quickly to messages that we see on a regular basis. After seeing the same warning for the fourth time, we dismiss it within two seconds (see Figure 3; Amer & Maris, 2007; p. 16). Again, not to belabor the point, but you can’t learn if you aren’t spending the time to process the contents of the message.

To conclude, nudges must be a component of a well-rounded and rigorous educational program. They are not the main dish, but a side.

Figure 3. The average dwell time for each exception message as it is shown multiple times.

Learn more about Proofpoint’s approach to human risk management and nudging.

References

Amer, T. S., & Maris, J. M. B. (2007). Signal words and signal icons in application control and information technology exception messages—Hazard matching and habituation effects. Journal of Information Systems, 21(2), 1-25.

Chi, M. T., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational psychologist, 49(4), 219-243.

Corbett, A. T, & Anderson, J. R. (1990). The Effect of Feedback Control on Learning to Program with the Lisp Tutor. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 12.

Hausmann, R. G. (2024, May 15). “Nudge Theory Alone Won’t Save Cybersecurity: 3 Essential Considerations.” Proofpoint.

Hausmann, R. G., Vuong, A., Towle, B., Fraundorf, S. H., Murray, R. C., & Connelly, J. (2013, July). An evaluation of the effectiveness of just-in-time hints. In International conference on artificial intelligence in education (pp. 791-794). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Koedinger, K. R., Corbett, A. T., & Perfetti, C. (2012). The Knowledge‐Learning‐Instruction framework: Bridging the science‐practice chasm to enhance robust student learning. Cognitive science, 36(5), 757-798.

Nokes, T. J., Hausmann, R. G., VanLehn, K., & Gershman, S. (2011). Testing the instructional fit hypothesis: the case of self-explanation prompts. Instructional Science, 39(5), 645-666.

Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on Formative Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153-189.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Nudge: The final edition. Penguin.