Introduction

In January 2020, Proofpoint researchers established an internal working group tasked with hunting for threats surrounding the 2020 US elections. Threat actors continue to attack organizations linked to the elections both directly and peripherally, and until very recently, the activity did not heavily use election-specific social engineering themes. It is only within the last month that we have observed actors significantly pivot to social engineering content centered on the election. However, this doesn’t minimize the threat to election-adjacent personnel or systems.

Recall the 2016 Democratic National Committee (DNC) compromise. The root cause was a generic “password reset” phishing message. Proofpoint continues to observe similar daily threat activity, though that activity does not appear to be targeting election-related organizations. For example, governmental organizations represent only a subset of individuals and organizations that received the same credential phishing campaign. There is no clear pattern to the overall collection of recipients or their verticals.

Hypotheses and methodology

We searched for election-themed threats across our customers, including federal, state, county, and city governments; third-party contractors directly responsible for implementing election controls; technology companies supporting digital voting assets, and news media and journalism outlets.

In addition to focusing on threats being delivered to election-related entities, our primary research goal was to identify email traffic using election-related themes for social engineering purposes. Proofpoint researchers expected that threat actors would likely attempt to impersonate legitimate campaign communications, deliver misinformation around voter registration, vote-by-mail, polling place location or procedures, and attempt to solicit political donations.

Beyond previously mentioned or reported threats, Proofpoint has not observed direct activity matching these expectations. We expected to identify landing pages congruent with these themes, possibly purporting to be an online voting registration portal, or a request for an absentee ballot. Further, we hypothesized we might find portals spoofing legitimate campaign websites either for phishing or to deliver malicious payloads, such as under the guise of an official campaign app. While we have not observed attacks across all these categories, we have recently observed spoofed online voter registration portals and email messages threatening recipients to “Vote for Trump or else!”

Observed activity in Proofpoint data

Legitimate but compromised sites via HTML injects

We have observed threats with election-related content on legitimate websites that have been compromised or are serving malicious advertisements. This isn't a case of actors specifically leveraging election-related content, but a potential threat to susceptible users with a propensity for news consumption.

In mid-July, we observed SocGholish HTML injects on a news organization’s site, which suggested to us that the site may have been compromised in some way. We confirmed that the compromised resource associated with a Wordpress theme was hosted on the site, which redirected to fake flash installer dialogues, leading to the download and execution of unknown malware. This threat was spread via legitimate automated newsletter emails from the news site linking to new compromised page. Messages were also sent from a Gmail address that appears to regularly email news links to several inboxes at the news organization. In this case, the subject of messages spreading this threat were a variation of a popular radio host’s comment on a Democratic plan to cancel the election with a link leading to an article of the same name presented in the message body.

Emotet and Ursnif

Beyond compromised website assets, malware that features automated thread hijacking has also driven routine activity that initially appears election-specific but is not. Compromises by Emotet, some Ursnif variants, and potentially other banking trojans lead to compromised inboxes. When these malware variants scan stolen emails, if “Re:” is detected in a subject, the malware can create a message to be sent to others in the email thread, complete with spoofed addresses appearing to be other legitimate participants in the email thread.

With Emotet’s scale and volume, some of the automated thread hijacking results appear to be highly targeted and personalized but are just part of the malware’s routine process. Researchers have observed a variety of cases of personnel directly related to the elections receiving responses to emails which contain election-related content that lead to Emotet.

Election-related domain registrations

Researchers also monitor for illegitimate election-related domain registrations. Proofpoint has enumerated over 10,000 domains involving typosquatting techniques or appending different words around a candidate name, such as “donaldtrumpangels[.]com”, “joebiden[.]club”, “donaldtrumped[.]tv”. These domains are then correlated against our threat data and email message data to identify an embedded link in a scanned attachment, used as a landing page hosting either a credential phishing portal or malicious download, or an intermediary redirection page or service. To date, only three of these domains have been identified in campaigns, and they were all associated with spam.

SMS data

We anticipated finding SMS attacks similar to those we anticipated for email. SMS analysis is different, however, from email analysis because it’s often impossible to identify the intended recipient. Knowing that many election-adjacent and election-related entities send alerts via SMS, we hypothesized we might identify election-themed phishing, solicitation of political donations, and misinformation around potential voting registration/location and vote-by-mail. At this time, Proofpoint has not identified SMS threats of this kind.

Figure 1: Example of an election-related automated text message

Notably, nearly every campaign or PAC is using a third-party vendor to handle their automated messaging. These services have millions of rotating phone numbers which serve as an extra layer of anonymization in determining the specific originator of any given message. This makes it difficult to determine if a given message is sent by an official campaign, by a PAC in support of that campaign, by some local grassroots effort making use of the same technologies.

Figure 2: Example of an election-related text message using URL shortening services

Use of URL shorteners is widespread, due to SMS character length restrictions and for the sake of human readability. Researchers have observed an overwhelming number of legitimate campaign messages using bit.ly redirectors. Bit.ly is open to reviewing and removing potentially malicious content hosted on their platform. While researchers have not identified malicious bit.ly activity, the threat of a malicious actor compromising a legitimate redirector or in spoofing legitimate campaign content with their own similarly patterned shortened links remains a possibility.

Mobile apps

Each of the major party presidential candidates have released a mobile app in hopes of engaging voters. Proofpoint researchers analyzed both apps to understand what information is collected, how it is used, why users need to be aware. Our analysis focused on version 2.4.2 of the Trump campaign app and version 2.3.0 of the Biden campaign app, though some earlier versions of each were also examined.

Both apps use a variety of third-party trackers and data sources, opening users to additional security risks. As a user’s data is shared with multiple platforms and services, there is a chance that it could be misused, leaked, or stolen. In particular, the Trump app’s heavy reliance on geolocation data increases a user’s exposure during movement or travel. The Biden app’s emphasis on contact information increases risk to personally identifiable information (PII) about the user and their contacts being shared or exposed.

Data sent to app servers and tracking services

Both apps make use of third-party tracking services, but they have different areas of focus and levels of granularity. While most mobile apps use some form of tracking, the extensive device and location details collected by the Trump app are notable; similarly, the contact and personal details collected by the Biden app are worth emphasizing.

Trump app

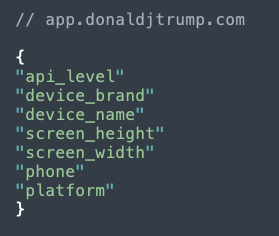

The Trump app provides articles and relevant social feeds to users. As they peruse the app, device and location data are gleaned and sent to various tracking services. It sends some basic information back to the app server:

Figure 3: Data sent to Trump app server

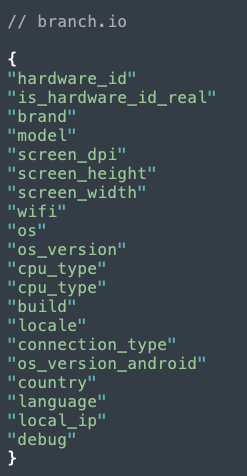

It sends some additional device details to Branch, a mobile engagement optimization tool:

Figure 4: Data sent from Trump app to Branch.io

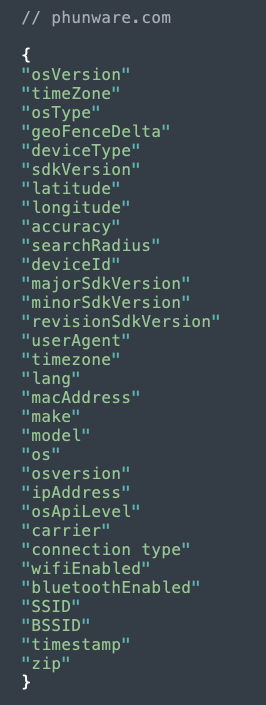

The Trump app also sends data to Phunware, the mobile development firm that developed the app. The latitude, longitude, SSID, and bluetoothEnabled data are especially notable because they allow for granular location tracking:

Figure 5: Data sent from Trump app to Phunware

Biden app

The Biden app focuses heavily on outreach, and thus, the user’s contacts. A ‘contacts’ tab in the Biden app encourages users to sync their phone contacts to the national voter file to “find people you know and encourage them to get involved.”

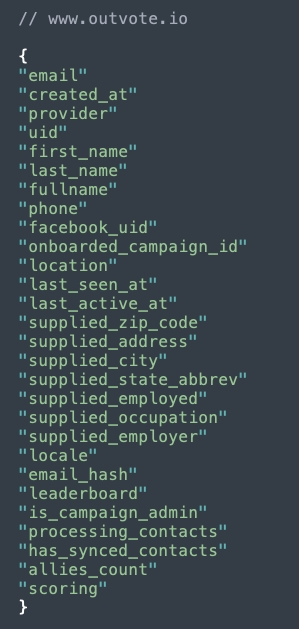

The Biden campaign has partnered with Outvote, a digital mobilization app that “empowers...you to create change both on and offline.” The following details about the user are sent to Outvote:

Figure 6: User data sent from Biden app to Outvote

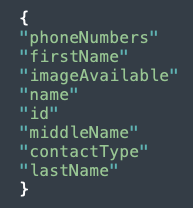

The following data about the user’s contacts is also sent to Outvote:

Figure 7: Contact data sent from Biden app to Outvote

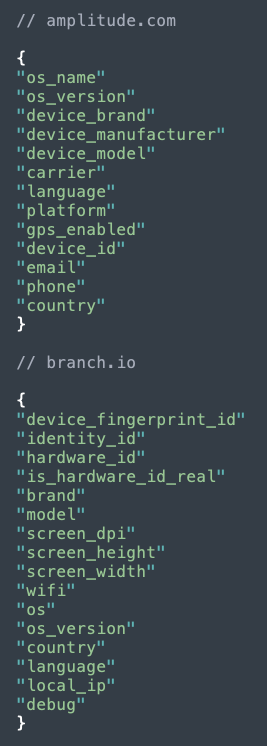

Like the Trump app, the Biden app also sends mobile OS and device data to Branch, but in addition it sends to Amplitude, a mobile product intelligence tool:

Figure 8: Data sent from Biden app to Amplitude and Branch.io

Contact syncing in the Biden app allows users to compare their contacts against a list of registered voters to identify any contacts who may not be registered to vote. Prior to September 11, 2020, it was possible to create a ‘fake’ contact with any name that would sync to the voter list and provide information about the voter to the user through the UI. Moreover, it provided more detailed information in the response than shown to the end user, like home address or political affiliation. According to subsequent review of this issue, it appears to be fixed and redacts sensitive data.

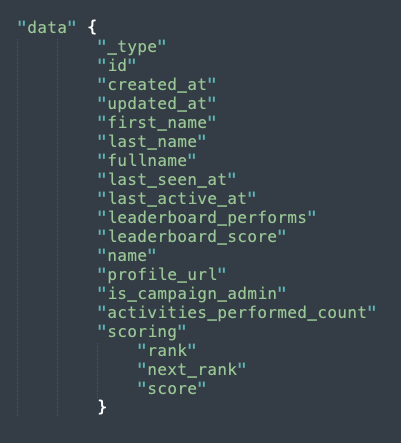

In addition to the current version of the Biden app, we also examined version 1.1.8. In that version, along with the data shown above, we also observed a list of “allies” returned in the response from Outvote when examining the app’s traffic. This appears to be a list of Biden supporters and volunteers, along with their volunteering rank (e.g., “New Recruit,” “Dedicated Volunteer,” “Activist”). The data also indicates how many activities the volunteer has performed, when they were last active on the platform, and their activity score.

Figure 9: Data sent in response from Outvote to Biden app

In the current version of the app, this data is no longer sent.

Both apps send some form of the mobile device ID to their preferred tracking services, which allows for tracking across different sessions and more targeted advertising.

Permissions

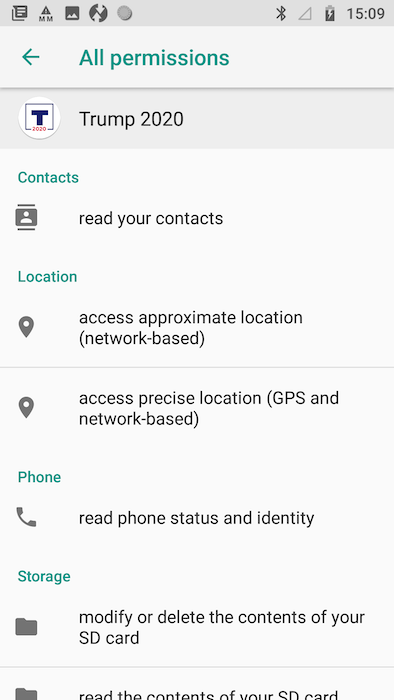

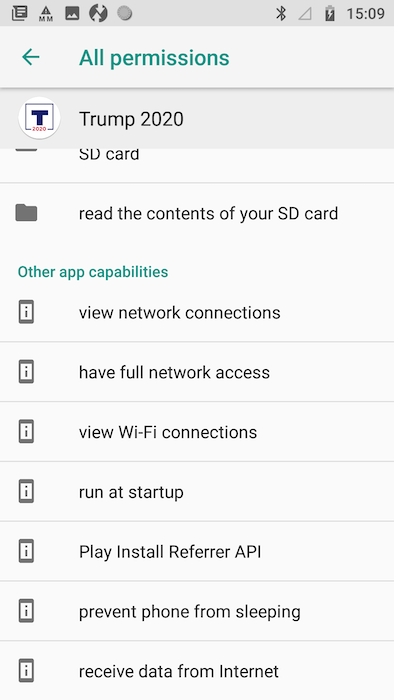

Trump app

Figure 10: Trump Android app permissions

These permissions allow the Trump app to, among other things:

-

Read your contacts

-

Read or modify contents of your SD card

-

Access the current cellular network information and the status of any ongoing calls

-

Access your location based on the network you’re connected to, and via GPS

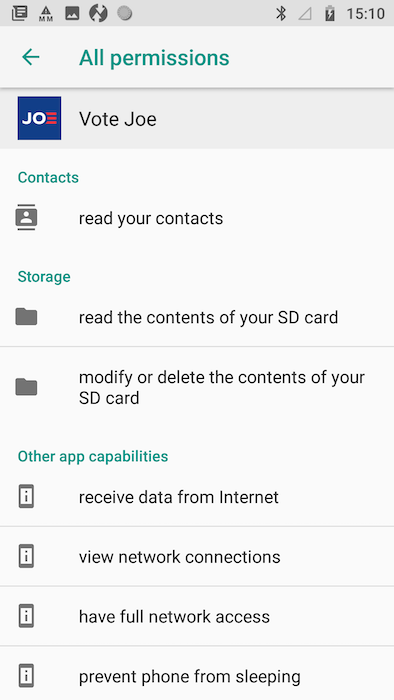

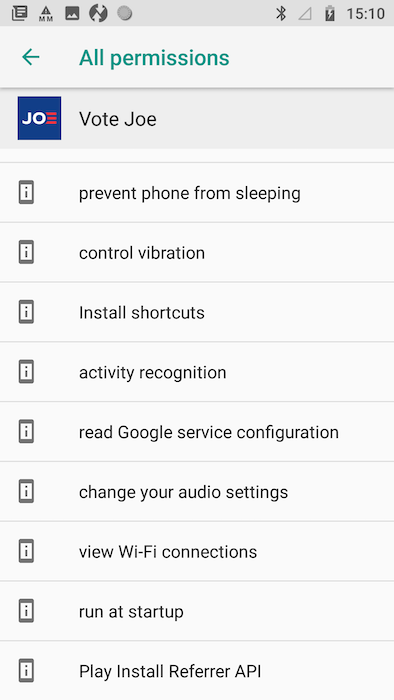

Biden app

Figure 11: Biden Android app permissions

These permissions allow the Biden app to, among other things:

-

Read your contacts

-

Read or modify contents of your SD card

While the Biden app requests more permissions overall, some permissions requested by the Trump app, like reading the phone state along with approximate and precise location, are particularly invasive.

At their core, these are data collection apps. One is more focused on contacts, while the other is more focused on user tracking, but they're both collecting nontrivial amounts of data. Contacts data, which each app requests access to, is especially valuable because it allows each campaign to create a clearer picture of voters’ social networks.

Conclusion

For this analysis, we examined email, SMS, and domain registration data, as well as the Trump and Biden mobile apps. Among these data sources, our team expected to find clear evidence of threats to election-related entities, or more general election-themed threats. While organizations both directly and peripherally linked to the elections continue to receive general threats, the activity directed at these organizations has not used election-specific social engineering themes. However, we have observed voter registration and political party-related themes in threats, though they have no clear targeting. More recently, we observed messages designed to intimidate voters into choosing a specific political candidate.

Based on our observations and careful review of the data, election-specific threats do not always appear to be election-themed. Though they can be, as in the cases of spoofed voter registration credential phishing pages or voter intimidation messages, even more generic threats could be effective against election-related entities.

Further reading

CISA Insights: Actions to counter email-based attacks on election-related entities