Table of Contents

A brute-force attack is when a hacker tries every possible password combination until they break into a system. It’s like trying every key on a ring until one finally opens the lock. These attacks work because they take advantage of a simple fact: with enough time and persistence, anyone can guess a password, especially if it’s weak.

Cybersecurity Education and Training Begins Here

Here’s how your free trial works:

- Meet with our cybersecurity experts to assess your environment and identify your threat risk exposure

- Within 24 hours and minimal configuration, we’ll deploy our solutions for 30 days

- Experience our technology in action!

- Receive report outlining your security vulnerabilities to help you take immediate action against cybersecurity attacks

Fill out this form to request a meeting with our cybersecurity experts.

Thank you for your submission.

What Is a Brute-Force Attack?

Brute-force attacks systematically guess passwords, login credentials, or encryption keys until finding the right one. There’s no skill involved; only determination and computing power do the heavy lifting.

These attacks don’t take advantage of weaknesses in your software or security vulnerabilities. Instead, they rely on automation and computational effort to go through millions or billions of possible combinations. A single computer can check thousands of password attempts per second, and attackers often use more than one computer at a time to speed things up.

Success depends entirely on your password’s strength and complexity. With today’s technology, a simple six-character password could be broken in minutes. But a 12-character password with a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols could take hundreds of years. Length works in your favour, as each extra character and symbol type exponentially increases the number of possible combinations that an attacker has to test.

The irony is that brute-force attacks are both very easy to do and very effective against weak defences. They’re highly successful if you have limitless time and resources, but in real life, they become impossible when passwords are long and complicated enough. Modern security frameworks emphasise strong passwords precisely because they make brute-force attacks nearly impossible, not just time-consuming.

How Brute-Force Attacks Are Carried Out: Main Attack Types

Brute-force is an umbrella term that includes several different ways to attack. These methods vary in complexity and speed, but follow the same basic idea of systematically testing credentials until something works. Knowing about these differences helps defenders understand what they’re really up against.

Simple Brute-Force

The most straightforward brute-force attack strategy is to simply try each possible combination of characters individually. A hacker may begin by trying “a” followed by “b”, etc., through “z”, then start with “aa”, “ab”, and so on until they get the password. This method uses a tremendous amount of computing resources but works relatively well against poorly selected passwords. A simple six-character password composed of only lowercase letters contains approximately 308 million possible combinations. Modern computers can test this many combinations within just a few minutes.

Dictionary Attacks

Rather than randomly trying a combination of letters, numbers, and symbols, dictionary attacks are lists of pre-existing common passwords and combinations that have already been used. Dictionary attacks include obviously weak password choices such as “password123” and “qwerty”, but also contain millions of previously compromised passwords from prior hacks. Dictionary attacks succeed because users choose memorable words and phrases—predictable patterns that attackers can exploit in seconds rather than hours.

Hybrid Attacks

Hybrid attackers begin by guessing a typical word or one of many passwords that have been compromised in the past. These attackers will then add numbers, special characters, or replace characters in a preplanned sequence to find the correct password. For example, a hybrid attacker may attempt to guess “password”, “password1”, “password!” and “p@ssword” as well as possibly millions of other similar versions. These types of attacks typically leverage partial information from prior breaches or knowledge of the target organisation’s password policy, such as length restrictions.

Credential Stuffing

While credential stuffing differs from brute-force attacks, attackers commonly use them together. The main difference is that brute-force “guessing” lacks context, whereas credential stuffers use an extensive collection of stolen usernames/passwords from previous breaches. Since most users reuse passwords across multiple sites, credentials stolen in a retail breach can unlock banking sites, email services, and business networks.

Offline Hash Cracking

If a hacker steals an organisation’s password database, they will typically receive a hashed version of each user’s password rather than the actual password. Hackers then hack that version of the passwords by using brute-force (trying every combination) outside of the hacked organisation’s secure environment.

Without alerting the targeted organisation, attackers can bypass account lockouts and attempt unlimited logins. Specialised hardware enables billions of password combinations per second, cycling through every possible hash until uncovering the correct credentials.

Application-Based Attacks

Attackers also use automated software when attacking live web applications by testing numerous username/password combinations in real-time. The software is essentially mimicking what a real user would do, but at the speed of a computer. Many web applications defend against these types of attacks using techniques such as rate limiting and account lockout. However, most attackers can successfully breach applications with limited security and/or poor monitoring.

Most attacks occur similarly: the attacker’s automated software attempts various credential combinations to identify a valid combination, and upon identification, uses the compromised account. Without additional security measures like multi-factor authentication, the attacker immediately gains full access to everything the compromised account can reach.

Post-Breach Actions

The compromised account’s access level and the application’s functionality determine what information attackers can steal. An attacker could compromise an employee’s or customer’s email accounts through phishing messages; install malware on internal systems; or gain access to a server process to intercept communications. In addition, if an attacker compromises a user with the highest-level credentials, they may be able to roam the network freely.

Compromised credentials are just the beginning. Attackers may install adware, redirect users to malicious servers, damage the company’s reputation, conduct espionage, or use the breached system to launch additional attacks.

An organisation may protect itself from various types of attacks (brute-force, dictionary, credential stuffing) by developing multiple layers of defence, while being aware of the different methods of hacking. It can also develop strong password policies to protect itself from brute-force attacks; monitor breach data and password block lists to defend against dictionary attacks; and implement multi-factor authentication to protect against credential stuffing attacks.

Popular Attack Tools

A human can type a few passwords into an application per minute, but a computer can process hundreds or thousands of password guesses a minute (depending on connection speed). As a result, attackers use automation to deploy brute-force attacks. Sometimes, they use their own scripts created in their favourite language, such as Python.

Examples of cyber attacker tools used to brute-force passwords:

- Aircrack-ng: A comprehensive suite of tools for auditing and securing Wi-Fi networks by cracking WEP and WPA/WPA2 encryption keys, creating fake access points, and capturing and analysing network traffic.

- John the Ripper: An open-source password cracking tool that supports a wide range of cipher and hash types, including Unix, macOS, and Windows user passwords, web applications, and database servers.

- L0phtCrack: A Windows password auditing and recovery tool that uses dictionary, brute-force, and hybrid attacks to recover passwords from password hashes.

- Hashcat: The world’s fastest and most advanced password recovery tool, capable of leveraging GPU power to crack a wide range of hashed passwords using various attack modes such as dictionary, combination, mask, and hybrid attacks.

- DaveGrohl: A tool designed for brute-forcing web applications, particularly useful for testing the security of web forms and login pages (not covered in the provided sources).

- Ncrack: A high-speed network authentication cracking tool designed for testing network services like SSH, RDP, and FTP by performing brute-force attacks (not covered in the provided sources).

- OphCrack: A Windows password cracker based on rainbow tables, known for its speed and efficiency in cracking Windows passwords.

- RainbowCrack: A tool that uses rainbow tables to crack password hashes by reversing cryptographic hash functions, significantly speeding up the cracking process.

- Cain and Abel: A multi-purpose password recovery tool for Windows that can perform various functions, including packet analysis, VoIP recording, and wireless network scanning, as well as dictionary and brute-force attacks on password hashes.

- Medusa: A parallel, modular, and login brute-forcer that supports many protocols, including HTTP, FTP, and SMB, designed to be fast and efficient for penetration testing.

In addition to password-cracking tools, attackers will run system vulnerability scanners to identify outdated software and discover information about the target application. Administrators should always keep public-facing servers updated and patched and use monitoring software to identify scans on the system.

Why Brute-Force Attacks Remain Relevant

Although there’s greater security now more than ever to combat cyber-attacks, brute-force is still a major threat to many organisations. According to Microsoft’s 2025 security report, more than 97% of identity attacks are password spray or brute-force attacks. These types of attacks can be advantageous due to how users behave, how technology functions, and how attackers profit from their attacks.

- Password dependence across systems: Many systems today still rely on password-based authentication, including web applications, SSH servers, and older technologies. As long as passwords remain the primary authentication method, brute-force attacks will continue to find viable targets.

- Weak password choices make defences less effective: Studies show that people tend to choose passwords that are easy to type and remember. A NordPass study found that “123456” and “password” are still two of the 10 most common passwords in the world. The average weak password can be broken in less than a second.

- Passwords reused across multiple accounts opens the door for hackers: Google and the University of California found that 65% of people do this. A single successful brute-force attack can unlock many systems, which is a high return on investment for attackers.

- Automation makes attacks possible: Cloud computing resources and botnets allow hackers to conduct massive brute-force attacks at relatively little expense. A single distributed botnet can test millions of credential combinations simultaneously, thereby exceeding the limit of attempts to be blocked by rate limiting or IP blocking.

- Brute-force as a way in: After gaining initial access to a system via a brute-force attack, hackers will often steal credentials to broaden their access, move laterally throughout the network, and ultimately steal data.

- Common attack surface on exposed services: In 2024, brute-force techniques increased by 12%, making up nearly 35% of all attack techniques observed in the Microsoft Azure environment. Hackers continuously scan and attempt to brute-force SSH, cloud, and Linux endpoints around the globe.

- Attackers don’t have to be very skilled to get in: Hackers use increasingly sophisticated tools and scripts to execute brute-force attacks. Attackers don’t have to be technology experts. Most hacking frameworks will automatically perform the entire process of conducting a brute-force attack on a target with weak security.

Common Targets and Use Cases

Brute-force attacks usually happen on systems where one set of credentials gives you access to a lot of valuable information. The patterns are known, but the effects are very different depending on where attackers are successful.

- Web application login portals (user accounts, admin consoles): Customers, employees, or administrators can easily find and access public-facing login pages, which makes them prime targets. If someone is able to brute-force their way in here, they could take over an account, expose data, or get full administrative control of the application.

- Remote access protocols (SSH, RDP, FTP, VPN): Services like SSH and RDP are regularly scanned and attacked with automated login attempts, sometimes just minutes after they are made available to the internet. Once attackers have remote access, they can stay there, install malware, or move deeper into internal networks.

- Databases or backend services that use credential-based authentication: Hackers really want to get direct access to databases or internal APIs that are only protected by passwords. In these situations, compromised credentials often mean instant access to sensitive records, transaction data, or proprietary information.

- Encrypted files, password-protected archives, encrypted data stores: When attackers steal protected files or backups, they may try offline brute-force or dictionary attacks against the encryption password. This is because encrypted files, password-protected archives, and encrypted data stores are all examples of protected files. If you use weak or reused passwords on these archives, even strong cryptography won’t work.

- Hashed password dumps from data breaches (offline cracking): Attackers can run large-scale brute-force and dictionary attacks offline with stolen password databases because there are no rate limits or account lockouts. Once those credentials are cracked, they can be used to log into other services, which leads to credential stuffing and other security breaches.

- Accounts with weak or default settings (old servers, legacy systems, IoT devices): Devices and systems that come with default passwords or aren’t up to date with security measures are often easy targets. Attackers often use scripts to try brute-force attacks against known default username-password pairs in order to quickly take over a lot of exposed hosts.

Detection, Warning Signs, and Red Flags

Most brute-force attacks begin with some obvious or simplistic behaviour that doesn’t seem to follow the normal actions of most individuals. As such, if your organisation identifies these behaviours early on during an attempted brute-force attack, you will have reduced the risk of that brute-force attack escalating into a larger issue.

One of the most obvious indicators of a brute-force attack is a high volume of failed login attempts from one IP address or from a very small range of IP addresses over a short time frame. Even though most organisations have implemented controls (e.g., locking out the account after so many failed login attempts), if the same account continues to experience a high volume of failed login attempts, your organisation should investigate those accounts further.

Another clear indicator of a brute-force attack is when an attacker attempts to log on quickly using a large number of different usernames, especially if the pattern of login attempts appears to be machine-generated. Large-scale use of stolen credentials typically signals either traditional brute-force guessing or credential stuffing.

You also may be looking at a brute-force attack if your authentication endpoint(s) have an unusual spike in traffic. A sudden increase in traffic to your login page or API authentication endpoint(s) that appears to be coming from an abnormal location or from a known malicious IP range typically means that an automated tool has been deployed as part of a brute-force attack.

If an attacker continually attempts to log in to your system, but their session behaves abnormally (e.g., credentials continue to be entered, no valid sessions are created, typical user resources do not load, etc.), it’s a clear indication of a brute-force attack.

Access attempts outside of normal business hours or strange login sequences can help fill in the gaps. Patterns like trying to log in to multiple accounts and failing, then successfully logging in to a different account, or alerts from WAF rules, anomaly detection, account lockouts, or rate-limiting controls can help confirm that what you are seeing is a coordinated attack and not just a mistake by a user.

Brute-Force Attack Prevention and Mitigation Best Practices

Several strategies are available to administrators to help them prevent and detect brute-force attacks. The first step is to create better password rules so that users can’t create weak passwords. Enforce strong, high-entropy passwords or passphrases that are long, unique, and resistant to guessing. Each additional character exponentially increases the search space and raises the cost of brute-force attacks. With strong password encryption, a computer would take several decades to finally brute-force a password.

The following strategies can also be used to stop brute-force attacks:

- Rate limit password attempts/login throttling: The application can limit the number of password attempts before locking the account and display a CAPTCHA when too many attempts are made. Limiting the attempts prevents automated brute-force attacks and makes running through hundreds of potential passwords infeasible.

- Account lockouts and progressive delays: This will disrupt the attacker’s continued brute-force attacks by temporarily locking the account after a set number of failed login attempts. Implementing progressive delays is also effective by locking the account for increasing periods after each failed attempt.

- Block suspicious IP addresses: If an IP address sends too many login attempts, the system could either block the IP automatically for a short while or an administrator can manually add it to a “blacklist”. This helps prevent repeated attacks from the same source. Modern controls often use reputation feeds, allowlists/denylists, and geo-based rules to tune how aggressively to challenge or block traffic.

- Use multi-factor authentication (MFA): MFA requires users to enter two forms of identification to sign in. The process uses knowledge, location, possession, and time factors to confirm a user’s identity, making it much harder for attackers to gain access even if they have the password. MFA dramatically reduces the value of brute-forced credentials because a stolen or guessed password alone is usually not enough to complete a login.

- Employ strong password policies and credential hygiene: Enforce strong, unique passwords that are difficult to guess. Passwords should be long (at least 10–12 characters) and include a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters. Regularly update and change passwords to reduce the risk of compromise. Encourage or enforce good credential hygiene, including no password reuse across services, periodic credential rotation for high-value accounts, and avoiding shared credentials across multiple users or systems.

- Use CAPTCHA, adaptive auth, or bot defences on public logins: Adding a CAPTCHA box to the login process can prevent automated scripts from attempting to brute-force passwords. CAPTCHA options include typing images of text on the screen, checking more than one image box, and naming objects. Increasingly, organisations pair CAPTCHA with adaptive authentication, bot-detection, and web application firewalls to profile traffic and challenge automation before it reaches the login flow.

- Monitor authentication endpoints and logs: Regularly monitor server logs for unusual login attempts and patterns that may indicate a brute-force attack. Set up alerts to notify administrators of suspicious activity in real-time. Focus on failed-versus-successful login ratios, spikes at authentication endpoints, unusual IP or geolocation patterns, and access attempts outside normal user or business hours.

- Maintain IP reputation controls: Use curated IP reputation, dynamic blocklists, and automated response rules instead of static blacklists alone, so your defensive posture can adapt as attacker infrastructure changes.

- Reduce the attack surface of accounts: Remove or disable old and unused accounts to reduce the number of potential entry points for brute-force attacks. Regularly audit privileged, service, and legacy accounts, tighten default configurations, and close or harden any exposed logins for older systems or IoT devices.

- Harden password storage with modern hashing: Use “salting” in cryptographic hashing to strengthen passwords. Adding random letters and numbers (salt) to passwords before hashing them makes it significantly harder for attackers to use precomputed tables (rainbow tables) to crack the hashes. Pair salting with slow, modern password hashing algorithms to raise the cost of offline brute-force attacks against stolen credential databases.

- Use strong cryptography for stored credentials: Use the highest available encryption rates, such as 256-bit, to protect system passwords. Robust encryption makes it much more difficult for brute-force attacks to succeed. Focus on well-vetted algorithms and configurations rather than custom schemes, and ensure keys and secrets are managed securely to avoid creating new weaknesses.

By implementing these password protection strategies, organisations can significantly reduce the risk of successful brute-force attacks and protect their systems and data from unauthorised access. Monitoring software detects brute-force attacks and alerts administrators of suspicious behaviour. When brute-force attacks are detected, the application could be under an account takeover attempt. These attacks could merit additional network reviews to determine if a data breach has occurred.

For enhanced security, it’s crucial to use strong, unique passwords for all your accounts. If you’re not sure where to start, try our password generator. It creates robust passwords that can help protect you from brute force attacks and other security threats.

How Proofpoint Can Help

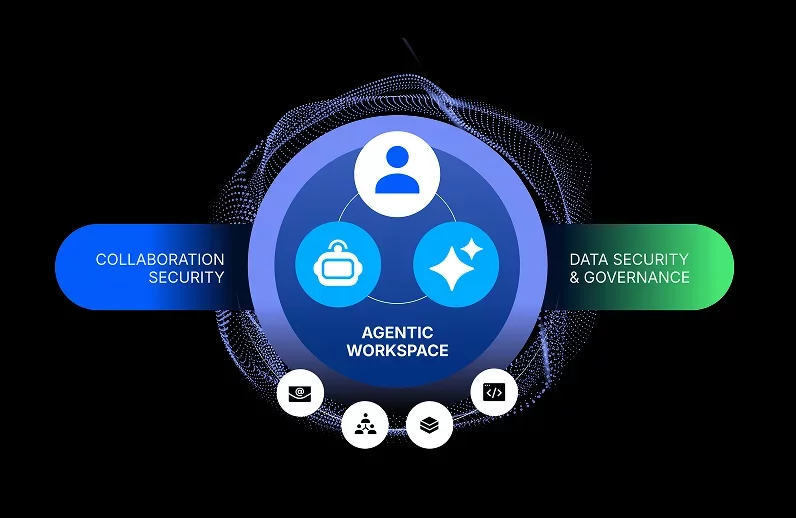

Proofpoint offers a comprehensive suite of cybersecurity solutions designed to protect organisations from various threats, including brute-force attacks. By leveraging Proofpoint’s advanced technologies and expertise, businesses can significantly enhance their defences against these relentless attacks.

Proofpoint’s Business Email Compromise (BEC) and Email Account Compromise (EAC) Protection solutions are specifically tailored to safeguard organisations against brute-force attacks targeting email accounts. These solutions employ a multi-layered approach to detect and prevent unauthorised access attempts, ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of email communications.

- Advanced threat detection: Proofpoint’s solutions leverage sophisticated algorithms and machine learning models to identify and block brute-force attacks in real-time. By analysing login patterns, IP addresses, and other behavioural indicators, Proofpoint can accurately distinguish legitimate access attempts from malicious ones.

- Adaptive access controls: Proofpoint’s adaptive access controls dynamically adjust security measures based on the risk level associated with each login attempt. This includes implementing rate-limiting, CAPTCHA challenges, and account lockouts to disrupt and prevent successful brute-force attacks.

- Comprehensive reporting and alerting: Proofpoint’s solutions provide detailed reports and real-time alerts, enabling security teams to monitor and respond promptly to potential brute-force attack attempts. This visibility empowers organisations to take proactive measures and mitigate risks effectively.

- Automated incident response: In the event of a successful brute-force attack, Proofpoint’s solutions can automatically initiate incident response actions, such as account lockouts, password resets, and notifications to affected users and administrators. This streamlined response minimises the potential impact and ensures swift remediation.

With Proofpoint’s protection, organisations can significantly enhance their defences against brute-force attacks, safeguarding their email accounts and sensitive data from unauthorised access. Proofpoint’s advanced technologies and cybersecurity expertise provide a comprehensive and proactive approach to mitigating the risks associated with these persistent threats. To learn more, contact Proofpoint.

FAQs

What is the difference between a brute-force attack and credential stuffing?

Without knowing anything about the password beforehand, brute-force attacks try every possible combination or common password pattern until they find one that works. Credential stuffing exploits password reuse by testing stolen credentials from past breaches across multiple sites. Both attacks automate login attempts, but credential stuffing leverages known-valid credentials while brute force guesses from scratch.

Can brute-force attacks be used against encrypted data, not just passwords?

Yes, attackers often use brute-force methods to get past passwords or encryption keys that protect files, archives, and data stores that are encrypted. When hackers steal encrypted databases or backups that are password-protected, they can run brute-force attacks offline without having to worry about rate limits or being locked out. The strength of the encryption key or password and the attacker’s computing power are the only things that determine whether these attacks will work.

Are long passwords always safe from brute-force attacks?

Long passwords make brute-force attacks computationally infeasible with current technology, but not impossible. A 12-character password with mixed case, numbers, and symbols could take hundreds of years to crack using brute-force. On the other hand, a simple six-character password could be cracked in minutes. But if that long password is found in leaked credential databases or follows patterns that are easy to guess, dictionary and hybrid attacks can still break it much faster than pure brute-force would suggest.

How does MFA protect against brute-force attacks?

Multi-factor authentication needs more than just a password to prove your identity. You might need a code from an authenticator app, a biometric scan, or a hardware token. Even if hackers manage to guess a password using brute-force, they still can’t log in without that second factor, which they usually can’t get through automated guessing. This makes MFA one of the best ways to protect against brute-force attacks because it goes against the idea that credentials alone give access.

What are signs that a brute-force attack is happening?

High volumes of failed login attempts from single IP addresses or tight IP ranges are among the clearest indicators, especially when paired with rapid, systematic attempts across many usernames. Unusual traffic spikes to authentication endpoints, login attempts from atypical geographies or suspicious IP reputations, and repeated failed attempts that never generate normal user sessions all suggest automated attack activity. Alerts from WAF rules, account lockout systems, or anomaly detection tools can help confirm that coordinated brute-force attempts are underway rather than simple user errors.

Does using a CAPTCHA stop brute-force attacks?

CAPTCHA can stop a lot of automated brute-force tools because it needs human interaction that scripts can’t easily copy. But determined attackers can get around basic CAPTCHA challenges by using CAPTCHA-solving services or more advanced bots. That’s why CAPTCHA works best as part of a layered defense. Using CAPTCHA with rate limiting, IP reputation filtering, and adaptive authentication provides better protection than just using CAPTCHA alone.

Should organisations disable login attempts after a certain number of failures?

Account lockouts after repeated failed attempts can halt brute-force attacks by stopping automated credential testing. But if lockout policies are too strict, they can give attackers a chance to lock out real users on purpose, so businesses need to find a balance between security and usability. Progressive delays that make wait times longer after each failed attempt, along with alerting and IP-based rate limiting, often offer better protection without making things harder for real users.