Table of Contents

A supply chain attack is a highly effective way of breaching security where attackers target third-party suppliers, vendors, partners, or software dependencies to compromise downstream organizations. It’s a cyber-threat that steals sensitive data, gains access to highly sensitive environments, or takes remote control over specific systems.

There are two types of supply chain attacks:

- Attacks on the software supply chain that target code repositories, open-source libraries, software update pipelines, and development tools to add harmful code to real applications.

- Attacks on the operational supply chain that take advantage of third-party service providers, such as managed security providers (MSPs/MSSPs), cloud vendors, or business partners who have special access to the networks they seek to target.

The most at risk are third-party suppliers or vendors, such as major software developers and hardware distributors, who build and ship components integrated into customer environments. Modern attack surfaces include SaaS platforms, integration APIs, contractor remote access, and open-source dependencies embedded in proprietary software. They’re generally carried out to gain access to targets downstream of the supply chain. These cyber threats can affect any industry, from the financial and government sectors to the oil and gas industry.

Cybersecurity Education and Training Begins Here

Here’s how your free trial works:

- Meet with our cybersecurity experts to assess your environment and identify your threat risk exposure

- Within 24 hours and minimal configuration, we’ll deploy our solutions for 30 days

- Experience our technology in action!

- Receive report outlining your security vulnerabilities to help you take immediate action against cybersecurity attacks

Fill out this form to request a meeting with our cybersecurity experts.

Thank you for your submission.

How a Supply Chain Attack Works

Supply chain attacks come in many forms, whether through email communications, vulnerable software misconfigurations, or malicious hardware attacks. In many cases, “threat actors take advantage of established financial relationships between businesses and their suppliers,” says Craig Temple, Senior Product Marketing Manager at Proofpoint. “It’s not out of the ordinary for suppliers to discuss terms or payments via email. If a bad actor can interject themselves at the right point in an email exchange or strike up an email conversation while impersonating someone, they can increase their odds of stealing payments or goods,” he adds.

Supply chain attacks in the technology sector target software vendors and hardware manufacturers. Attackers search for unsafe code, unsafe infrastructure practices, and unsafe network procedures that allow the injection of malicious components or provide pathways to downstream targets. When a build process requires several steps from development (or manufacturing) to installation, an attacker (or group of attackers) has several opportunities to inject malicious code into the final product or establish persistent access through legitimate vendor credentials.

Supply Chain Attack Lifecycle

There is a clear pattern to how supply chain attacks happen:

- Determine the supplier’s weak point: Attackers look into vendors with many customers and identify security gaps in their development pipelines, cloud environments, or remote access tools.

- Compromise supplier environment: Attackers break into the vendor’s systems and persist using phishing, stealing credentials, or exploiting vulnerabilities.

- Insert harmful code or gain access: Attackers insert backdoors into software updates, steal vendor credentials that let customers in, or break into APIs used for integrations.

- Spread to downstream customers: Malicious code spreads through legitimate update channels, or stolen credentials give direct access to customer environments.

- Execute payload: Once attackers gain access to target networks, they steal data, spread ransomware, spy, or establish long-term bases for future operations.

Some manufacturers, vendors, and developers build products used by thousands of clients. An attacker who can breach one of these suppliers could potentially gain access to thousands of unsuspecting victims, including technology companies, governments, security contractors, and more. Instead of breaching just one targeted organization, a supply chain attack gives an attacker the potential to obtain access to numerous large and small businesses to silently exfiltrate extensive amounts of data without their knowledge.

The impacts are increasing across the board. Third-party involvement now accounts for 30% of breaches (double the rate in previous years), according to Verizon’s 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report. And they’re also considerably more expensive than the average data breach, with supply chain incidents costing an average of $4.91 million and taking up to 267 days to detect and contain, according to recent findings.

In a hardware supply chain attack, a manufacturer can install a malicious microchip on a circuit board used to build servers and other network components. Using this chip, the attacker can eavesdrop on data or obtain remote access to the corporate infrastructure. In a software-level supply chain attack, a malicious library developer can change code to perform malicious actions within their client’s application. An attacker could use the library for cryptojacking, stealing data, or leaving a backdoor to remotely access a corporate system. Modern attacks also exploit open-source dependencies with known vulnerabilities, SaaS vendor misconfigurations, and MSP remote-monitoring tools.

In many of the biggest supply chain threats, email fraud is the primary vector used to launch the attack. Business email compromise (BEC) works well for attackers who do their due diligence on their target. That’s because they can email key employees (e.g., finance) to instruct them to pay an invoice or send money. The sender’s address looks like that of the CEO or owner, and it’s written in a way that sounds urgent to the recipient. In some scenarios, the attacker compromises an email account for an executive and uses it to send phishing emails to employees within the organization.

When vendors are hacked, attackers switch from supplier networks to customer environments using legitimate access credentials and trusted integration points. This makes it extremely difficult to pinpoint the threat actors. From a legal and compliance perspective, supply chain breaches often require both the vendor and the affected customers to notify the relevant parties. Companies need to determine whether a vendor’s unauthorized access to their systems is a breach that must be reported under GDPR, HIPAA, or state privacy laws.

Types of Supply Chain Attacks

Supply chain attacks can affect any business that uses third-party vendors or integrates software and services from outside the company. Modern attacks exploit many parts of the technology stack and business relationships.

Software Attacks

Attackers break into software development and distribution channels to reach end users. Dependency poisoning attacks package repositories such as NPM and PyPI by uploading malicious libraries with names similar to those of real libraries. Adding backdoors to popular libraries that thousands of apps depend on is what open-source tampering is all about. As is evident by the SolarWinds attack, software update hijacking takes advantage of legitimate update methods to distribute malicious code through trusted channels.

Operational Attacks

Service providers that grant special access to certain vendors also become prime targets. When a vendor’s credentials are compromised, attackers can gain access to customer environments via support portals or remote administration tools. MSP and MSSP compromises are especially vulnerable because companies manage security infrastructure for multiple clients simultaneously. Third-party insider misuse happens when employees of a contractor or vendor use their authorized access to steal data or create backdoors.

Hardware and Firmware Attacks

Injecting harmful components into circuit boards during manufacturing is an example of a physical supply chain threat. A bad manufacturer can add extra parts to listen in on data and send it to attackers. Compromises at the firmware level persist even after reinstalling the OS and are hard to find.

Cloud and SaaS Attacks

Cloud service providers use shared responsibility models: if one side makes a mistake, both sides are at risk. API integrations between SaaS platforms create trust relationships that attackers exploit. When a SaaS vendor is hacked, any applications that use those APIs become vulnerable. Salesforce misconfigurations in 2025 put over a billion records at risk for many downstream customers.

Data and Identity Attacks

Business email compromise attacks hurt vendor relationships by gaining access to company email accounts and using them to eavesdrop on conversations and trick people into divulging personal information or sending money to accounts controlled by the attacker. Third-party identity trust abuse takes advantage of federated authentication, which lets organizations log in to partner systems with their own credentials. When attackers break into partner identity providers, they can get into all the organizations that are connected.

AI and ML Attacks

Machine learning models introduce new supply chain risks. One common threat involves poisoning training datasets by injecting malicious data during model training to introduce backdoors or bias in model outputs. When companies use pre-trained models from third-party sources without verifying their behavior, they create model supply chain dependencies. Open-source AI frameworks and model repositories pose risks analogous to those found in conventional software supply chains.

What Are the Impacts of Supply Chain Attacks?

The impact of a supply chain attack could devastate corporate revenue and sever vendor relationships. More specifically, they could result in:

- Operational downtime and disruption: Supply chain attacks can cause major operational troubles for a business, leading to costly delays and crippled productivity. When threat actors compromise software system updates or MSP tools, they can shut down systems for all end users at once.

- Data breaches, exfiltration, and espionage: In many supply chain attacks, especially hardware-based attacks, the malicious code eavesdrops on data and sends it to an attacker-controlled server. Attackers can breach data that passes through a system infected with malicious code, including potentially high-privileged account credentials for future compromises. Supply chain compromises often target intellectual property and customer databases to gain a competitive advantage or for nation-state espionage.

- Malware installation: Malicious code running within an application could be used to download malware and install it on the corporate network. Attackers could install ransomware, rootkits, keyloggers, viruses, and other malware using injected supply chain attack code.

- Financial impact: A targeted organization could lose millions if an employee is tricked into sending money to a bank account or paying fraudulent invoices. Beyond direct fraud, organizations face incident response costs, forensic investigations, legal fees, system remediation, and potential ransom payments. Business interruption compounds losses when critical systems remain offline during recovery.

- Reputational erosion and trust loss: When supply chain attacks affect the quality and reliability of an organization’s products or services, the outcome can severely damage its reputation, resulting in lost customer or vendor trust and loyalty. Customers question security practices and move to competitors. Partners reassess relationships and impose stricter vendor requirements.

- National security implications: Nation-state actors pose greater supply chain risks to critical infrastructure sectors, including energy, defense, and government. When military systems, power grids, or telecommunications networks experience hardware or software failures, they become strategically weak. These events are less common than commercial attacks, but they have serious geopolitical consequences.

What Are the Sources of Supply Chain Attacks?

Supply chain attacks are a growing concern for organizations, primarily due to how diverse and complex they are. Attack surfaces span software, services, hardware, and human relationships that organizations depend on daily. Some common sources of supply chain attacks include:

- Commercial software vendors: Because many companies use the same software vendor and solutions, a supply chain attacker who can penetrate a software company’s system or compromise their product’s integrity will gain access to many targets. Software vendors with large customer bases are high-value targets because a single compromise can cascade to thousands of downstream organizations.

- Open-source supply chains: Attackers can target open-source software projects and inject malicious code into the codebase, which will be distributed to users who download the software. NPM, PyPI, and Maven are package repositories that host millions of libraries that developers use without vetting them very carefully. Attacks that compromise maintainer accounts or confuse dependencies take advantage of this trust.

- Cloud and SaaS platforms: SaaS vendors and cloud service providers handle and store customer data on shared infrastructure. Multiple accounts can be exposed if there are misconfigurations, API vulnerabilities, or compromised vendor admin accounts. Attackers take advantage of the transitive trust that comes from integration points between platforms.

- Managed service providers (MSP/MSSP): IT service providers often have exclusive access to customer networks to monitor, patch, and respond to incidents. MSP compromises are catastrophic because attackers get administrative credentials for all of their clients’ portfolios. When MSPs are hacked, remote monitoring and management (RMM) tools can be used to execute attacks.

- Contractors and third-party insiders: Temporary workers, consultants, and vendor employees can sometimes access sensitive systems and data. These insiders can steal information intentionally, or they might become unintentional accomplices when their credentials are compromised. More and more, supply chain problems are caused by third-party insiders misusing their access.

- API ecosystems: Many modern apps use dozens of third-party APIs for things like accessing accounts, processing payments, adding information, and analyzing data. Each API integration is a trust relationship in which problems with the upstream provider affect the downstream consumers. Attackers often breach access through compromised API keys or tokens.

- Software build pipelines: Attackers can infect legitimate apps to distribute malware by accessing source code, building processes, or updating mechanisms. They can compromise the CI/CD pipeline by injecting malicious code during automated builds that propagate through legitimate software update channels.

- Code-signing infrastructure: Attackers can steal code-sign certificates or sign malicious code to make it appear legitimate. This bypasses security controls that trust signed executables from known publishers.

- Hardware and firmware: Attackers can compromise hardware or firmware during manufacturing, allowing them to insert malicious components into the product. Firmware-level implants persist through OS reinstalls and operate below where most security tools can detect them.

- Logistics and OT partners: Companies that use operational technology are at risk in their supply chains from industrial control system vendors and logistics providers who handle physical supply chains. These partners usually have network access, allowing them to monitor equipment or manage inventory.

Organizations need to be aware of these sources of supply chain attacks and take steps to mitigate the risk. This can include implementing security measures such as multi-factor authentication, encryption, regular security audits, and vetting and monitoring third-party vendors and suppliers.

Who Is Vulnerable to Supply Chain Attacks?

Supply chain risk is a vulnerability that every business using third-party vendors, software, or services faces. Risk has less to do with size and more to do with how complicated and secure the dependency is.

Because they hold sensitive data and have large vendor ecosystems, industries that are heavily regulated, such as financial services, healthcare, and government agencies, are at higher risk. Attackers target these areas because successful breaches yield valuable data and open new avenues for extortion. When vendor compromises trigger notification requirements, compliance obligations compound the situation.

Technology and software companies rely on complicated dependency chains that connect open-source libraries, cloud platforms, and development tools. A single broken package in NPM or PyPI can spread to thousands of apps. Industrial control system vendors and logistics partners need network access to monitor equipment in manufacturing and operational technology environments.

Mid-market companies are especially at risk because they don’t have enough resources to vet vendors or respond to incidents. They don’t have specific programs to deal with supply chain risk, but they do have valuable customer information and intellectual property that hackers want.

When global companies work with vendors in multiple countries, they are more exposed to risk. Managed service providers that handle infrastructure for many clients are high-value targets because one breach can give access to all of a customer’s portfolios. Open-source projects require very careful security checks, as any changes could make them vulnerable to users who come after them.

Real-World Examples

Several real-world attacks have already been launched against the supply chain, but aren’t widely known to the general public because they supply developers and operations. These examples primarily impact corporate administrators who must contain, eradicate, and remediate the vulnerabilities left by vendors affected by supply chain attacks.

A few real-world examples that affected large corporations include:

- MOVEit: This 2023 supply chain attack exploited an SQL injection vulnerability (CVE-2023-34362) in MOVEit’s software, a managed file transfer platform operated by Progress Software. The attack by the Cl0p ransomware group affected over 2,600 organizations worldwide, including British Airways, the BBC, Zellis, and the Minnesota Department of Education, compromising data from approximately 85-90 million individuals. Attackers targeted the file transfer layer, where sensitive data is aggregated during transmission, and then used stolen data for extortion.

- 3CX: In early 2023, this cyber attack targeted the 3CX Desktop software, a voice and video conferencing app. The attack, carried out by the North Korean hacking group UNC4736, affected at least 130 organizations worldwide, including several critical infrastructure organizations in the United States and Europe. The attackers first compromised a 3CX employee through trojanized X_Trader trading software, then used that access to inject malware into 3CX’s build environments, demonstrating a cascading supply chain attack.

- SolarWinds: In 2020, attackers injected a backdoor into SolarWinds’ update distribution process, leaving corporate and government production servers open to remote access. Numerous organizations fell victim to data breaches and security incidents. The malicious code was digitally signed and distributed through legitimate update channels, compromising approximately 18,000 organizations.

- Kaseya: The REvil ransomware group exploited a SQL injection vulnerability (CVE-2021-30116) in Kaseya’s VSA remote monitoring and management (RMM) software in July 2021, deploying ransomware to upwards of 1,500 downstream businesses managed by MSPs, allowing attackers to demand $70 million from MSP customers. The attack demonstrated how MSP software creates force-multiplication opportunities by providing access to multiple customer environments simultaneously.

- Codecov: Attackers compromised the Codecov Bash uploader. In 2021, attackers extracted credentials from a misconfigured Docker image and modified the script to exfiltrate environment variables from customer CI/CD pipelines. With malicious code injected into its scripts, attackers eavesdropped and stole customer data, including AWS keys, API tokens, and authentication credentials, for approximately three months before detection. The attack succeeded because modifications were deployed to production without corresponding source code commits.

- XZ Utils: In early 2024, a sophisticated multi-year campaign nearly inserted a backdoor (CVE-2024-3094) into major Linux distributions. An attacker using the identity “Jia Tan” spent years building maintainer trust before injecting obfuscated malicious code into XZ Utils versions 5.6.0 and 5.6.1 that would compromise SSH authentication. The backdoor extracted a malicious object file from disguised test data during compilation, demonstrating nation-state-level persistence in supply chain targeting.

- eslint-config-prettier: In 2025, attackers compromised maintainer credentials through phishing and published malicious versions (8.10.1, 9.1.1, 10.1.1, 10.1.7) containing Windows-targeting malware. The attack exploited npm’s post-install lifecycle scripts to execute malicious code and affected over 14,000 packages that declared eslint-config-prettier as a dependency. Automated dependency update tools like Dependabot merged the malicious updates without scrutiny, highlighting risks in automated supply chain processes.

- Okta Support System: In October 2023, attackers compromised an Okta employee’s personal Google account, then used malware on the employee’s work laptop to access Okta’s customer support system. The attackers extracted session tokens from HAR (HTTP Archive) files that customers had uploaded to support tickets, gaining administrative access to 134 customer organizations, including 1Password and BeyondTrust. The breach persisted for nearly three weeks before detection, demonstrating how third-party support systems become high-value attack vectors when processing sensitive diagnostic data.

- Polyfill.io: After Funnull, a Chinese company, bought the polyfill.io domain and CDN service in February 2024, the service started adding harmful JavaScript to more than 100,000 websites that used scripts from cdn.polyfill.io. The malicious code sent mobile users to scam sites and enabled hackers to gain access through a backdoor. This shows that relying on third-party hosted resources can be risky.

Best Practices to Protect Against Supply Chain Attacks

Because supply chain attacks target developers and manufacturers outside of your organization’s control, they are difficult to stop. Security teams must implement defense-in-depth strategies that assume compromise at the vendor level and focus on limiting blast radius and detecting anomalous behavior.

Although supply chain attacks originate outside your control, you can employ the following enterprise-focused prevention controls:

Zero Trust Identity and Access

Implement continuous authentication and authorization for all users, applications, and devices rather than trusting authenticated entities by default. This architecture assumes that all access requests—including those from software updates, third-party integrations, and vendor tools—could be malicious and requires verification at every transaction, preventing lateral movement even when initial credentials are compromised.

Vendor Access Segmentation

Isolate third-party vendor access to dedicated network segments with restricted permissions and monitor all vendor activity separately from internal operations. Segment vendor connections by function and criticality, ensuring that MSP tools, support systems, and contractor access cannot reach sensitive production environments or move laterally across your infrastructure.

Third-party Risk Governance

Establish formal vendor risk assessment programs that evaluate security posture, incident response capabilities, and supply chain practices before onboarding and throughout the vendor relationship. Require vendors to provide attestations, security questionnaires, and proof of controls, such as SOC2 reports, and include breach notification clauses and security requirements in contracts.

Dependency and Software Bill of Materials (SBOM)

Keep detailed records of all software components, libraries, and dependencies used by your applications and infrastructure. This will help you quickly find and fix vulnerabilities. Create and monitor SBOMs for both the software you build yourself and software made by other parties. This requires tracking transitive dependencies and using tools to identify known vulnerabilities, harmful packages, and unexpected changes in dependency trees.

Patch and Update Pipeline Security

Before deploying software updates, verify their legitimacy to check digital signatures, checksums, and provenance. Also, stage updates in separate test environments before rolling them out to production. Use automated checks to ensure that updates are legitimate, don’t let updates install themselves without being checked first, and watch for signs that update mechanisms have been hacked, such as certificate problems or unexpected changes to binary files.

SaaS Security Posture Management

Continuously monitor cloud application configurations, permissions, and integrations to detect misconfigurations, overprivileged access, and unauthorized third-party connections. Use SSPM tools to audit OAuth grants, API tokens, and service account permissions across your SaaS ecosystem, revoke unnecessary integrations, and enforce least-privilege access to prevent credential-based supply chain attacks.

Behavioral Analytics for Identity and Insiders

Use user and entity behavior analytics (UEBA) to set standards for normal access patterns and identify abnormal actions like data access from unusual accounts, credential use from places you wouldn’t expect, or activity outside of normal hours. Watch for signs of compromised credentials, such as travel scenarios that don’t make sense, access to novel resources, and automated tool use that could mean attackers are using stolen tokens or hijacked service accounts.

DLP for Data Exfiltration via Supply Chain Paths

Implement data loss prevention controls that monitor and limit the movement of data through CI/CD pipelines, development tools, support systems, and third-party integrations. Set DLP policies to flag when credentials, API keys, environment variables, and sensitive files are exfiltrated through common supply chain channels—such as package uploads, HAR file submissions, and cloud storage syncing.

IR Playbooks for Vendor-origin Incidents

Create specific incident response plans for supply chain breaches that include rules for talking to vendors, ways to contain third-party software, and decision trees for isolating affected systems. Set up clear runbooks for situations like compromised vendor credentials, malicious software updates, and downstream attacks from managed service providers. These should include pre-written communication templates and rules for keeping evidence.

Supply Chain Risk Assessment

To understand how your organization could be vulnerable to a supply chain attack, you must first conduct due diligence and perform an internal risk assessment. After the SolarWinds supply chain attack, many organizations realized the importance of risk assessments to protect the internal environment from these third-party threats.

A supply chain risk assessment involves a systematic process by which an organization identifies, assesses, and mitigates the risks associated with its supply chain. This involves identifying and documenting supply chain channels, including suppliers, plants, warehouses, logistics, and other relevant components.

You should also categorize vendors using classification frameworks based on their access level, data sensitivity, and criticality to business operations. Then evaluate the likelihood and potential impact of each identified risk. Inventory all SaaS applications (including shadow IT and third-party integrations) to understand data exposure pathways and identify critical-path vendor dependencies where a single compromise could disrupt core business functions.

A risk assessment doesn’t just identify risks, but it also helps the organization design and manage them. Risk mitigation requires proper cybersecurity controls and a zero-trust environment to stop threats properly. In many cases, authorization controls and user privileges need to be redesigned to reduce risk. Assessments should calculate residual risk by evaluating vendor-provided security controls, attestations, and historical security posture to determine whether inherent risks have been adequately addressed.

AI and Software Supply Chain Security

The rise of AI and machine learning has created new ways for hackers to attack supply chains that go beyond just relying on software. Companies that use AI systems now need to treat training data, model artifacts, and ML frameworks as important parts of the supply chain that need the same level of care as regular software components.

- Training data and dataset integrity: AI models inherit their weaknesses from the training data they use, making data provenance a supply chain issue. Attackers can poison training datasets by adding malicious samples that cause models to misclassify certain inputs or leak sensitive information. Compromised data collection pipelines may also add backdoors that open under certain conditions.

- Model artifacts and dependency chains: Pre-trained models you download from places like Hugging Face or PyTorch Hub are examples of supply-chain dependencies that could contain backdoors or malicious inference logic. Serialization formats, such as pickle files and ONNX, can run any code when deserialized. This makes them vulnerable to attacks similar to those in traditional software supply chains.

- Open-source ML library risk: Popular ML frameworks like TensorFlow, PyTorch, and scikit-learn rely on large dependency trees that have the same npm and PyPI poisoning risks as traditional software ecosystems. Supply chain attacks on ML libraries can disrupt model training pipelines, steal private training data, or introduce harmful inference behavior into thousands of downstream AI apps.

To reduce AI-specific supply chain risks, organizations must also expand SBOM practices to include model provenance, check the sources of datasets, and sandbox model deserialization.

How Proofpoint Can Help

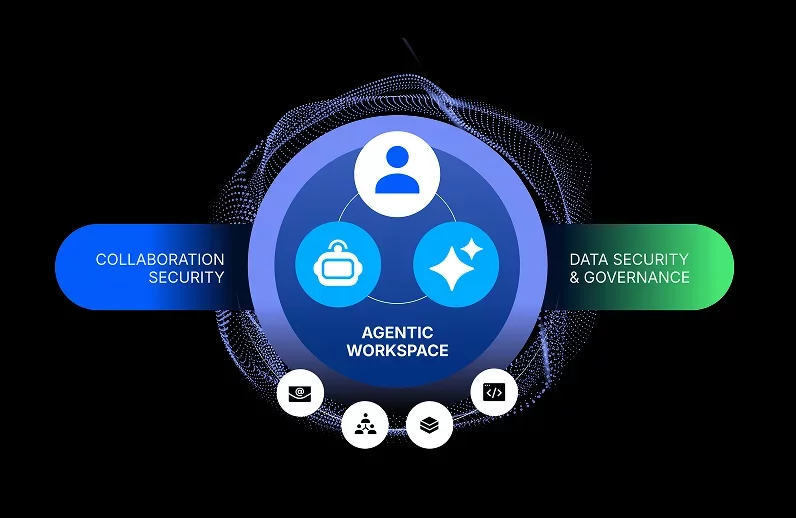

Proofpoint protects against supply chain attacks by covering all possible attack vectors, both human and technical. The platform’s behavioral analysis features monitor users and third-party insider threats to identify compromised credentials, unusual access patterns, and vendor account takeovers that indicate a supply chain breach.

Multi-channel data loss prevention tracks the movement of sensitive data across email, the web, cloud apps, and endpoints to prevent credential theft, API key exfiltration, and unauthorized data transfers through CI/CD pipelines and support systems. These are common methods attackers use to access the supply chain. Additional security awareness training helps employees learn about supply chain-specific threats, such as business email compromise, vendor impersonation, invoice fraud, and credential phishing campaigns.

Proofpoint’s solutions also integrate with compliance and risk management workflows, giving security teams a clear view of how third parties communicate and vendors access data. With this transparency, organizations can enforce vendor access policies and meet regulatory requirements while also spotting early signs of supply chain risk.

To learn more, contact Proofpoint.

The latest news and updates from Proofpoint, delivered to your inbox.

Sign up to receive news and other stories from Proofpoint. Your information will be used in accordance with Proofpoint’s privacy policy. You may opt out at any time.