Overview

As a center of government, business, and population, France has long been the target of a wide variety of cybercrime. Recently, however, Proofpoint researchers have tracked a number of threats, propagated through both email and exploit kits, with French targets that are uncommon in other regions. These include banking Trojans like Gootkit and Citadel/Atmos as well as a variety of phishing schemes targeting credentials for everything from national healthcare services to online banking to mobile phone providers. Moreover, the prevalence of the French language in multiple regions around the world has made French lures versatile tools for targeting francophone regions such as Belgium, Switzerland, and Canada.

Analysis

Banking Trojans

Gootkit is a banking Trojan that uses web injects to capture credentials from infected users. It may also steal sensitive financial information from the victim's email. Gootkit has generally been observed targeting France, Germany, Italy, and Canada, but has also occasionally been distributed with web injects for UK and Polish banks. Initially discovered in July 2014, multiple researchers have noted the similarities between Gootkit’s injects and those used by the Zeus banking Trojan.

Attackers deliver Gootkit via both exploit kits and email. We primarily observe email delivery through malicious document attachments that contain macros or "double-click to run" OLE packager objects.

In either case, when executed, the malware starts an explorer.exe or svchost.exe process and injects into it. It then downloads additional components using HTTPS on port 80. Gootkit also injects code into browsers in order to perform man-in-the-browser (MITB) attacks.

In addition to MITB injects, Gootkit uses a filter for grabbing sensitive information from emails. An example filter from an instance of Gootkit is shown below:

emailfilter":[{"from":"*paypal*","to":"","subject":"","body":""},{"from":"*chase*","to":"","subject":"","body":""}]}

Gootkit targets the following list of processes for injection:

- explorer.exe

- safari.exe

- chrome.exe

- opera.exe

- iexplore.exe

- lsass.exe

- mozilla.exe

- firefox.exe

- firef.exe

- maxthon.exe

- msmsgs.exe

- myie.exe

- avant.exe

- navigator.exe

- thebat.exe

- outlook.exe

- msimn.exe

- thunderbird.exe

- iron.exe

- dragon.exe

- epic.exe

- seamonkey.exe

One particular campaign, detected on December 13, included French, Belgian, and Italian targeting, using the following French-language lure document:

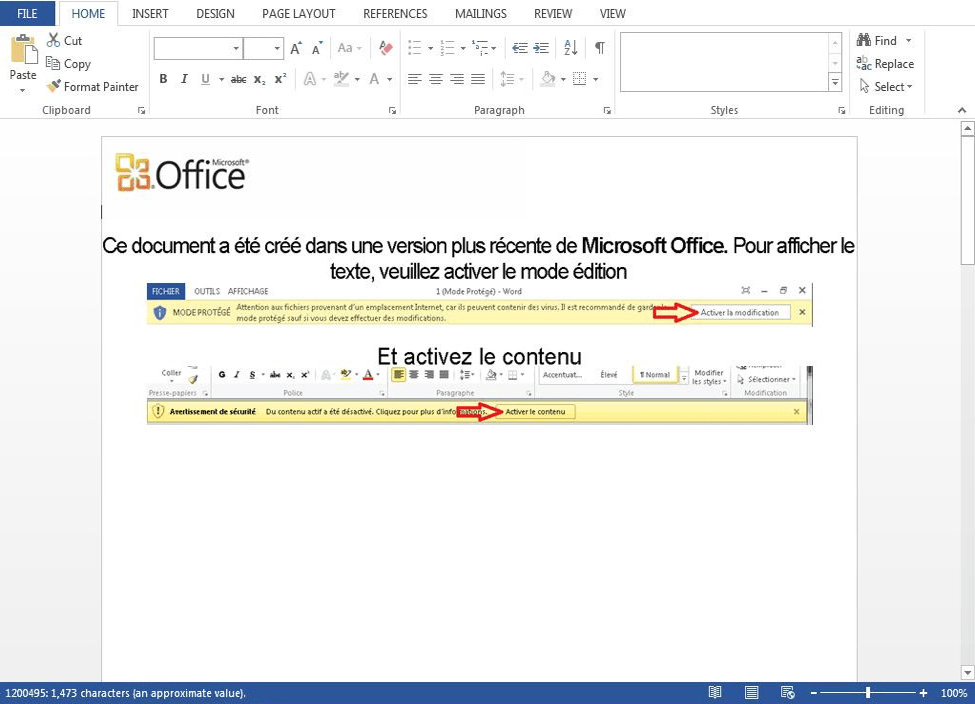

Figure 1: French-language Gootkit lure document with embedded macros

The lure is a Microsoft Word document with a header explaining that it was created in a "more recent version of Microsoft Office". As with the Enable Content button in English versions of Word, when the user clicks the "Activer la modification" button, a malicious macro executes and downloads Gootkit.

Other similar campaigns have also used French-language lures to distribute Gootkit but were global in their targeting, extending their reach and utility beyond France to the large number of francophone countries and citizens abroad.

The Dridex banking Trojan also remains active in regional campaigns across Europe, including France. Dridex dominated email-borne malware in 2015, and for a time targeted France almost exclusively during July 2015, it re-emerged for more targeted, smaller-scale attacks in the latter half of 2016. Dridex botnet ID 120 is generally targeted at French, British, and Irish interests.

One recent campaign included messages containing attachments with filenames such as "statement 52694.doc" or "customer info 87859.doc" (random digits). The attachments are Microsoft Word documents containing macros which, if enabled, download this instance of the Dridex banking Trojan.

Citadel is a relatively old banking Trojan, first discovered in 2011 and descended from the Zeus banker. Like Gootkit, Citadel has often been observed targeting French interests. In 2016, a new variant dubbed Atmos emerged. Both Citadel and Atmos target financial data with web injects taken from Zeus, but also capture personal information as well.

In a November 2016 campaign, Proofpoint researchers examined an instance of Citadel focusing on keywords and file extensions related to:

- ATM and SWIFT software and transactions

- Accounting software

- E-currency

- Gaming

Email messages sent as part of this campaign were written in French and contained URLs linking to RAR compressed .vbs scripts that installed Citadel.

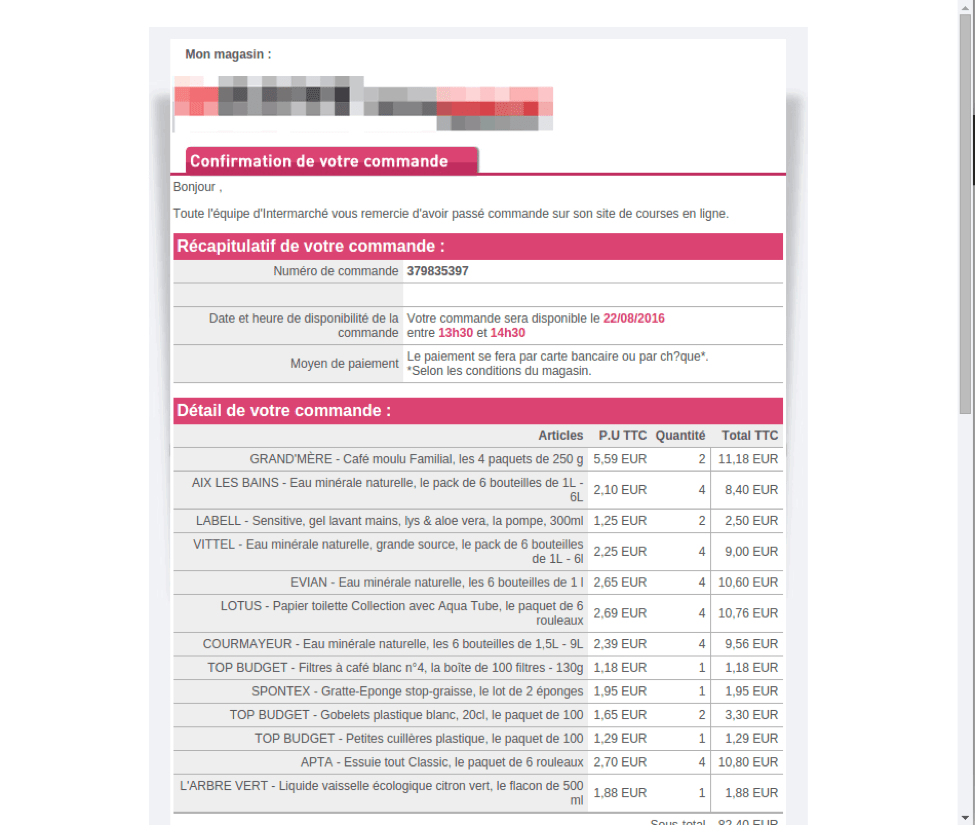

In another Citadel/Atmos campaign, attackers attached an HTML decoy order confirmation (Figure 2) for a French online grocer contained in a self-extracting archive. When recipients open the archive, it opens in a browser window; once closed, a vbs file declared in the SFX archive launches, installing the malware.

Figure 2: Decoy order confirmation for a French online grocer

Exploit Kits - LatentBot/Graybeard

Exploit kit (EK) traffic dropped off dramatically in 2016. However, some EKs remain active, including a French-targeted instance of the RIG EK. Proofpoint researchers observed RIG installing SmokeLoader on vulnerable PCs which, in turn, installed Pony Loader. The final payloads delivered by Pony in this case were LatentBot (aka Graybeard) and TeamViewer remote control software.

LatentBot is a Trojan capable of taking control of infected systems, stealing data, remotely monitoring system activity, and corrupting infected hard drives. It is also quite difficult to detect because it leaves few, if any, indicators of compromise behind.

Phishing

Credential phishing is a common attack; in France, as elsewhere, threat actors often leverage well-known organizations and entities, creating lookalike websites and using stolen branding to obtain specific information from victims. Victims are often led to these phishing sites via convincing emails with embedded URLs, stolen branding, and a compelling call-to-action. Phishing attacks target a wide variety of personal and financial information, including:

- Online banking credentials

- Telecommunications and webmail logins

- Personal health and financial details, including tax records

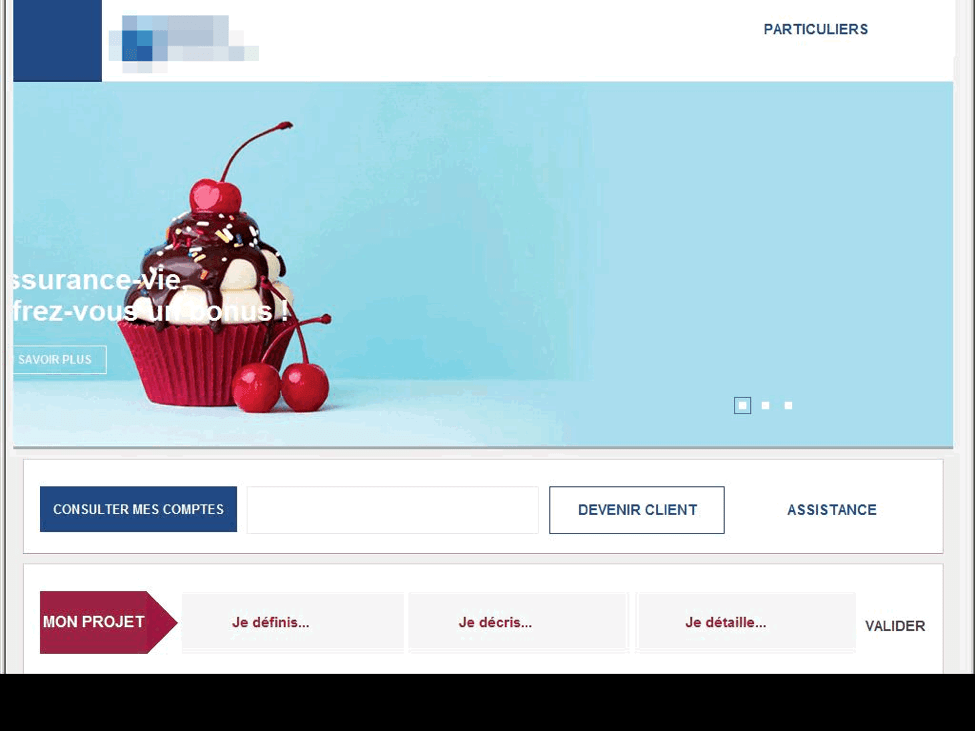

Banking credentials are an understandably common target of phishing scammers. Figure 3 shows a fraudulent version of a French online banking site designed to steal victims' banking credentials.

Figure 3: Fake French online banking site

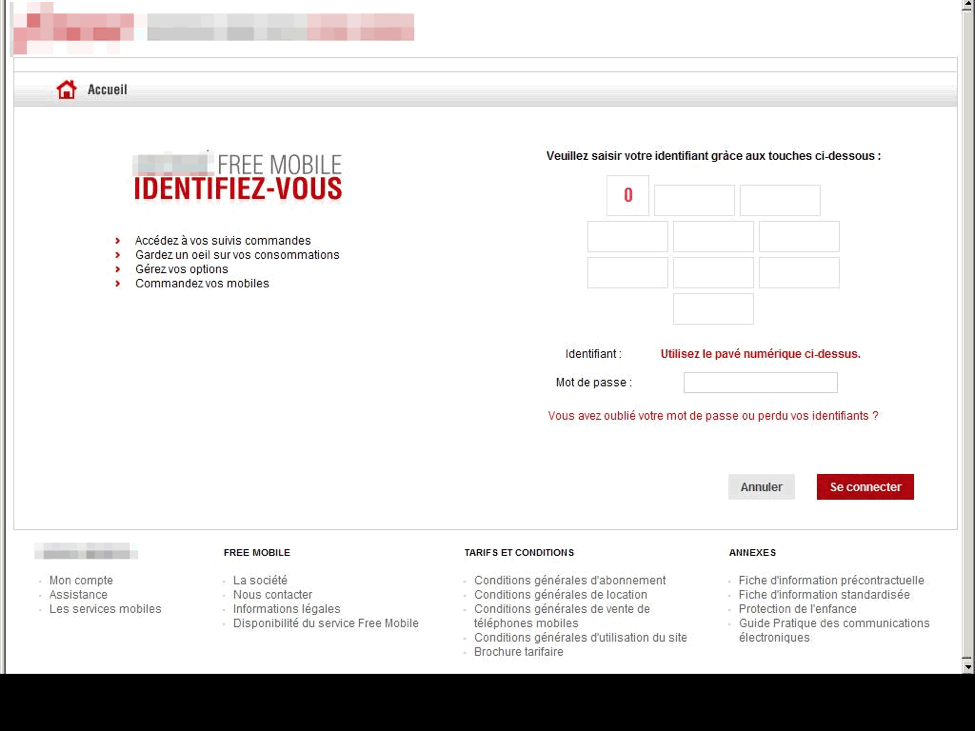

Proofpoint researchers have also observed phishing attacks targeting telecommunications accounts. One such campaign employs unsolicited emails to lure victims to credential phishing websites for a range of telecommunications institutions. The phishing emails rely on HTML attachments with URLs linking to the fraudulent telecom account login page and may also include a direct URL linking to the phishing page.

When the user enters their credentials in the fraudulent login page, the credentials may be sent to an external site controlled by the attacker, saved in a text file on the same server for later retrieval, or emailed to an attacker-controlled email address. The phishing site frequently redirects victims to the real TI login page, making it appear that the victim's login failed, at which point they simply log in again to the legitimate site, not realizing their credentials have been compromised (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Telecommunication phishing site

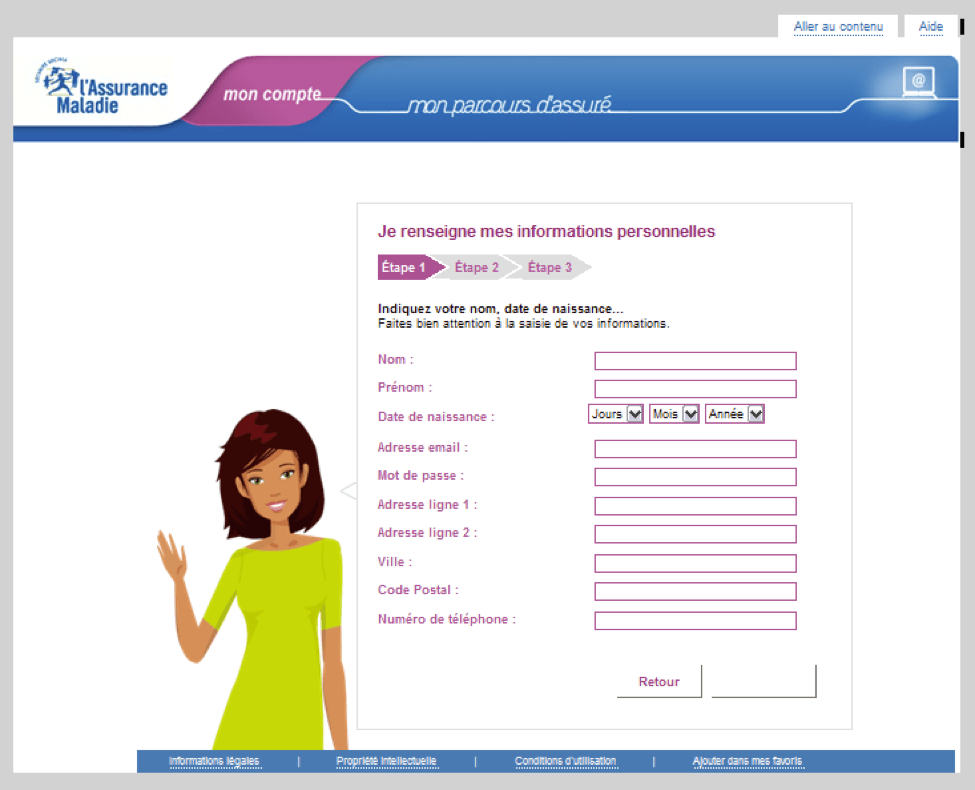

Phishing attacks extend well beyond attempts to steal webmail and online banking logins, however, and health and insurance schemes in particular are effective tools for capturing a wide range of valuable personal and financial details. Ameli.fr provides reimbursement for basic health care for French citizens. Phishing attacks related to Ameli.fr involve attempts to steal a victim’s personal information through fake Ameli.fr notifications of repayment. In this particular attack, the actor crafts fake Ameli.fr pages and hosts them on a compromised server, then embeds the URL for this page in a phishing email. The messages frequently – but not exclusively – use a “Payment Warning” lure that informs the recipient they must update their information. The login page carries graphics, marketing copy and branding very similar to those of a legitimate Ameli.fr page.

Figure 5: Fake Ameli.fr page

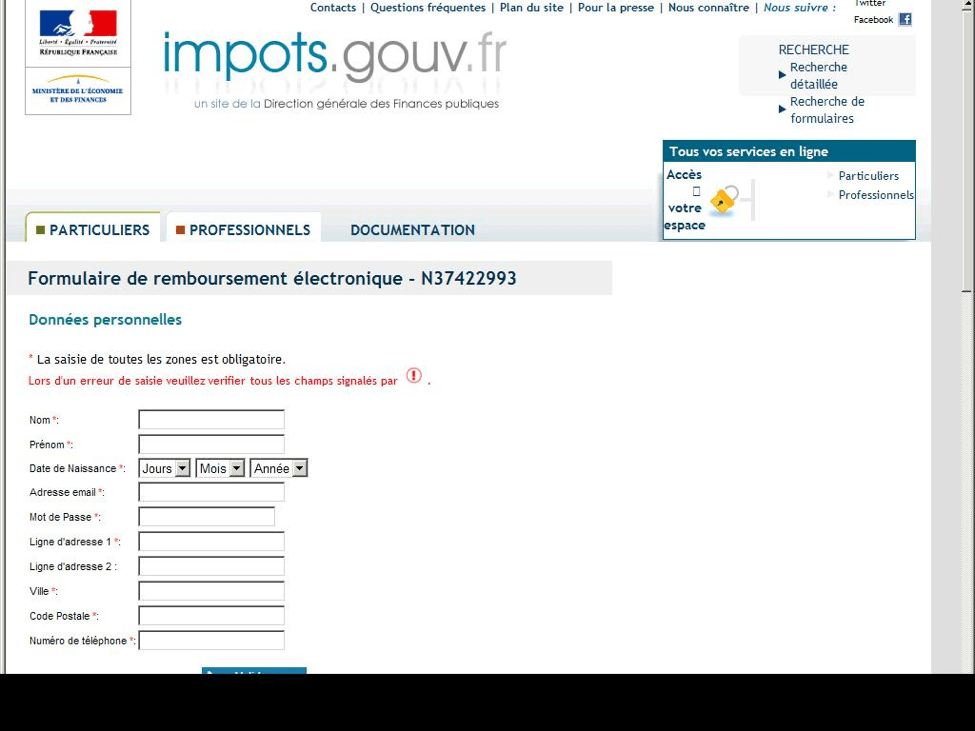

Other French government sites like the national tax service (impots.gouv.fr) are also ready fodder for attackers. Phishing lures themed after tax and government communications can drive increased responses by capitalizing on the ‘brand’ of the central or local government. The fake site shown in Figure 6 asks for a victim's tax service username and password to process a tax refund. To actually receive the refund, the site claims that users must enter their credit card information, netting phishers both login credentials and a credit card number, and this site also collects banking information.

Figure 6: Fraudulent French government tax refund phishing site

This threat of phishing that uses government-themed lures is not unique to France, and responses have varied from nation to nation, and even between local or regional governments. One potential example of an active response to this challenge comes from the UK government, through its newly founded National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), who provided with clear recommendations for its agencies to prevent and block consumer phishing.

Conclusion

Phishing attempts and attacks with banking Trojans are neither new nor unique to the French threat landscape. Organizations and individuals worldwide face these threats on a daily basis. However, French citizens and companies, as well as those in other French-speaking regions, frequently see malware that is uncommon elsewhere in the world and experience sophisticated credential phishing tied to specific government services.

Many of these attacks have been going on for years, suggesting that attackers continue to find success and financial rewards, leaving significant room for improving cyber defenses and overall awareness of cybercrime.

Throughout 2016, many European government bodies (such as in the UK and the Netherlands) have been driving various cyber security initiatives, including the mandated adoption of DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication Reporting and Conformance) authentication to secure email communication to its citizens – something the French authorities ought to consider considering the success of its UK counterparts, HMRC.