Over 90% of cyber attacks require user interaction. This means simple user actions—like errant clicks and misused passwords—can have severe consequences. With stakes this high, the need to eradicate these behaviors can’t be understated.

To get to the heart of the issue, Andy Rose, Proofpoint resident CISO, EMEA, recently sat down with Dr. BJ Fogg, Ph.D., a behavior scientist at Stanford University, to discuss the science behind behavior and how habits can be made and broken. Dr. Fogg is also a best-selling author and creator of the Fogg Behavior Model.

Here are some highlights from their conversation:

Rose: I’d like to start off by asking you to explain the Fogg Behavior Model and the concepts that underpin it.

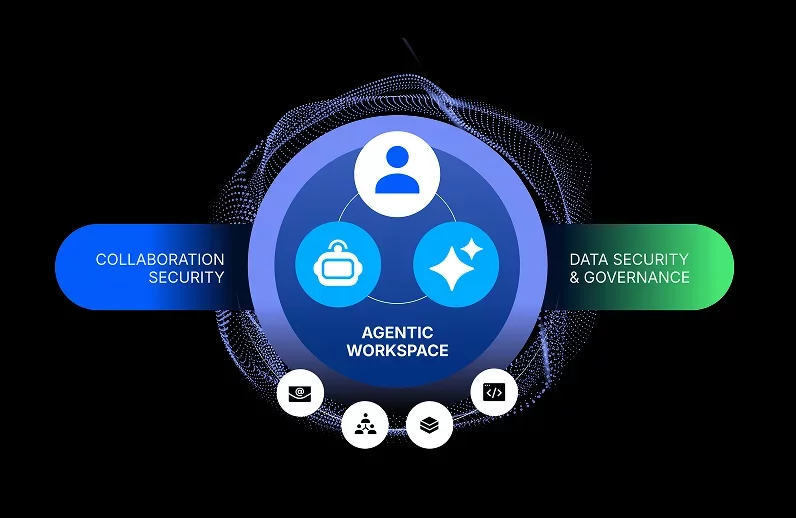

Fogg: Absolutely. This model is a universal model for all behavior types of all ages and all cultures. The model demonstrates that behavior happens when motivation, ability and prompt come together in the same moment. That’s the motivation to do that behavior, the ability to do the behavior and the prompt to do the behavior.

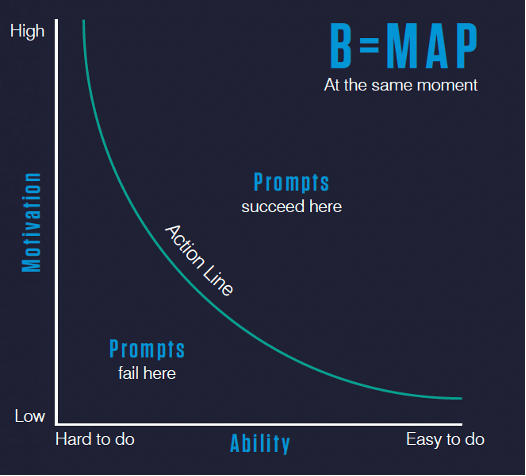

An illustration of the Fogg Behavior Model. Source: behaviormodel.org.

Let’s say you want somebody to donate to the Red Cross. If someone is super motivated to do so, and it’s easy to do, there’s a high likelihood that they will do so when prompted. Now, say that somebody doesn’t like the Red Cross and it’s hard for them to donate. Then, they’re unlikely to do so when prompted.

Between the ranges of motivation and ability is a threshold called the action line. If someone is anywhere below the line, when prompted they don’t do the behavior. And if they’re above, they do. That, in short, is the Fogg Behavior Model.

All specific human behaviors come down to motivation, ability and prompt. If any one of those is missing, the behavior will not happen. With this model, you can analyze and decide what’s missing.

You also wrote a book on the same subject, Tiny Habits. I know it’s intended to help individuals change their own behavior. But what do cybersecurity professionals have to do differently to apply this model en masse?

There’s a different way of thinking about it at scale, but it still comes down to what is the specific behavior we want people to do. And where do people stand in terms of motivation, ability and prompt, and what’s lacking to get people to do—or not do—these behaviors?

You can go in both directions. You can add a prompt or increase motivation, but you can also remove a prompt or make something harder to do. Either way, specificity changes behavior.

So saying, “Be cyber safe!” is a generalization. Instead, you need to be as specific as possible—when you see this kind of thing in this kind of email, do this specific behavior. You need to almost over-explain.

Behavior is broken down into three essential elements.

If I had to pick one thing to focus on after specificity, it would be to ask: “How can we change the difficulty of this behavior to encourage or discourage certain actions?” Sometimes, we can’t change motivation very reliably. But we can make things easier or harder to do—and we can do that at scale.

Let’s talk about the motivation side. We’re always telling people what to do, how to do it and what to look for. But these days, training tends to leave out the consequences of a behavior. How do we bring motivation and consequences into a security awareness program without overdosing on punishment and killing morale?

You need people to align a required behavior with something a user already wants—a motivator. This could be a promotion, status, looking good to their kids and so on. We see this all the time. For example, people don’t want to walk on a treadmill necessarily, but they want more energy and improved health.

So the key is to find something they already want and align your desired behavior with that. Where that’s not possible, you need to shift the ability or the prompt component and use those levers. But if you can—this is the maximum number one in my book—help people do what they already want to do.

Does that link back then to the popularity of gamification? Is that a way to create a desire to do something?

Yes. It is possible to create ways to motivate. And often that’s called gamification. It can be done well, and it can be done poorly.

For example, I’m not a fan of leaderboards. Because how many people feel successful when there’s a public leaderboard? One, maybe two. The vast majority feels unsuccessful. So you need to be careful with the techniques you use to lift motivation and make sure they have broad appeal.

Now, let’s talk about prompts. What tips can you give us on how to create effective and enduring prompts that people will continue to engage with?

That’s a hard question. There’s no magical way. If you’re prompting somebody over and over, they can quickly become blind to it, so prompts must be well-timed. You don’t want to prompt somebody to do something when they can’t do it. If they are super motivated to take a training module, but they can’t at the time they receive your prompt, that can be frustrating. So ideally, you’re prompting a person when they’re both motivated and capable.

With a large population, then it gets trickier. So you need to do the best you can with the information you have and act on it accordingly. Let’s say there is a cybersecurity incident at another company and it’s all people are talking about. Guess what? People are going to be more motivated than usual. And if you have them block off some time on their calendar, they have more ability to do it.

To touch on content again, lots of security professionals are creating it to communicate prompts and awareness messages. How can they create content that recipients will want to come back to again and again?

Let me start with what not to do. I call this the “Information-Action Fallacy”: If we just give people information, that will change their attitude, which will then change their behavior.

This sounds very logical. But it’s not really what works in the long run. Why? Because people believe what they want to believe. Information doesn’t reliably change attitudes. And even if it does, that doesn’t reliably change behaviors.

So it’s better to take a behavior and align it with what they already want to do. That way, you don’t necessarily have to first change attitudes to change behaviors. So to answer your question, when people do a behavior and feel successful, that then changes how they think about themselves.

That’s why it’s really important to have a feedback loop. If someone reports a phishing email to the security operations center, or they do the right thing, you really want to be acknowledging that as quickly as you can, right?

Yes, the timing of that feedback matters a lot. You can’t wait 30 days and then offer a little badge or acknowledgement. That’s an incentive, but it’s not a reinforcer. The emotion, the feeling of success, needs to happen very quickly.

How about measurement? If you’re trying to create a culture of security, how do you create a dashboard or metric that can be reported up to the board to show your success?

Well, certainly there’s quantitative measurements we can do with digital systems. But I’m not an expert on that. From a psychological perspective, what you are left with is self-report.

I would certainly look at measuring a shift in identity this way. One question I’ve used for over 10 years in the Tiny Habits program is to say, ‘I’m the kind of person who…’ and let people fill in the blank. This is a good way to measure people’s confidence or self-efficacy over time.

BJ, it’s been an absolute pleasure talking with you. In closing, do you have any final takeaways or recommendations for the security awareness training people who are reading this?

Yes. The good news is there’s a system behind human behavior. You don’t have to guess. You can systematically analyze, you can systematically design, and you can test and iterate and improve. And systems give you confidence in what you’re doing. You don’t have to wonder if you’re on the wrong track. You just learn the system and apply it.

Learn more from Dr. Fogg and explore his new book, Tiny Habits.

Discover New Perimeters—Protect people. Defend data.

Want to read more articles like this one? Access the latest cybersecurity insights in our exclusive magazine, New Perimeters. This publication is available to browse online, download to read later or receive in print directly to your door.

You can get your free copy of New Perimeters, the exclusive magazine from Proofpoint, here.