Overview

In 2016 and 2017, the results of three major national elections in the United States, France, and the United Kingdom all correlated with the volumes of spam referencing the winning candidates. In each of these three elections, the winning candidate or party appeared in higher volumes of election-related spam than their opponents, reinforcing the idea that spammers use candidates with the strongest brands in their lures. With Germany’s national elections just around the corner on September 24, Proofpoint researchers conducted a similar investigation of spam volumes with subjects related to German political parties and the key figures in each. As with previous elections, we compared trends in spam volumes with ongoing opinion polling and newsworthy events through the last several months of the election cycle.

If we take spam subject volumes as being predictive, as they have been in the last US, French, and UK elections, then recent trends suggest that new coalition possibilities in the German government are unlikely to emerge on September 24. Rather, based on spam subject volumes, the election will likely result in a continuation of the current “grand coalition,” despite the apparent lack of enthusiasm for it from any of its members or the public at large.

Background

Although the German political landscape is marked by a much more diverse set of parties and candidates than politics in the United States, the current election and existing government coalitions are dominated by the CDU/CSU, led by current Chancellor Angela Merkel, and the SPD, led by Martin Schulz. Other minor parties include the “Alternative for Germany” (AFD), “The Left” (LINKE), “Alliance 90/The Greens” (GRUEN), and the “Free Democratic Party” (FDP).

Analysis

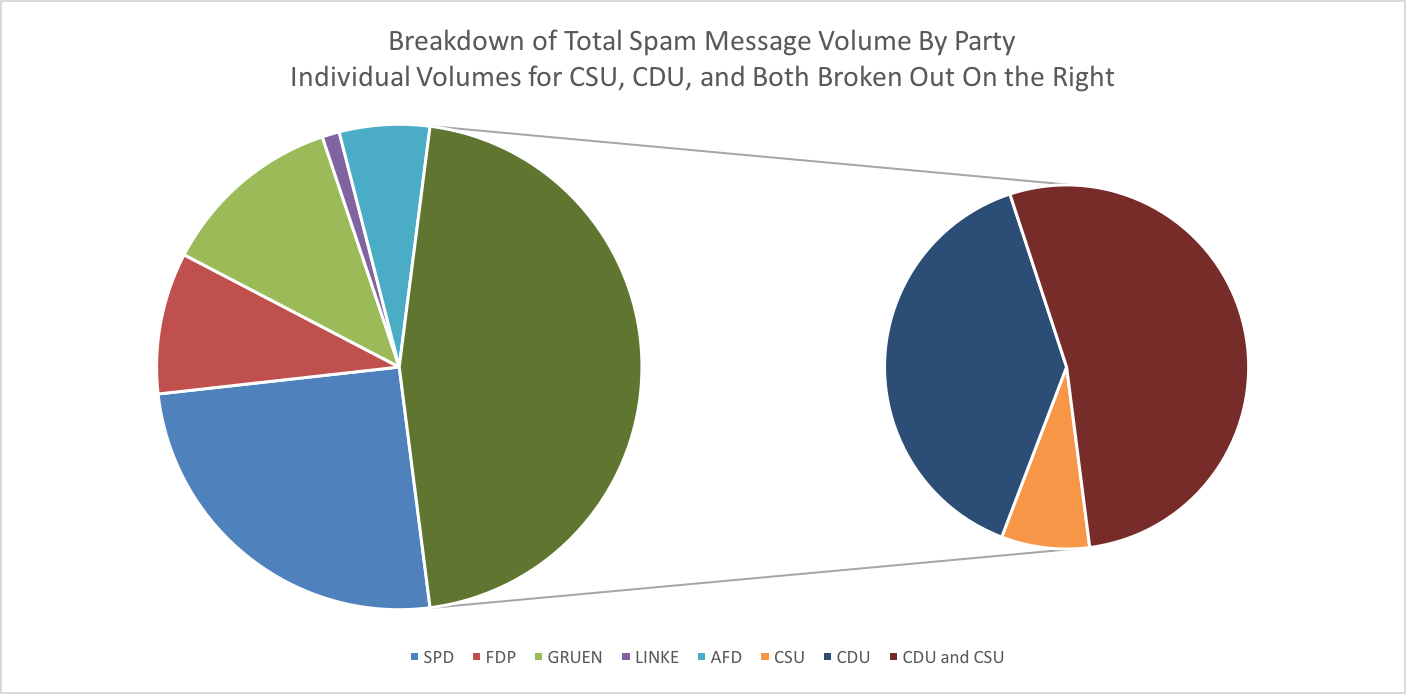

We configured filters to capture both spam and legitimate email associated with each of these parties, as well as the national candidates associated with each. Results are grouped by party. Note that spam associated with just the CDU (the Christian Democratic Union, led by Angela Merkel), just the CSU (the Christian Social Union, which is active only in Bavaria), and just search terms “Angela Merkel” and “Merkel” are grouped with CDU/CSU as these are functionally equivalent at the national level. Total spam message volumes by party, including a breakdown of the contributions to CSU-, CDU-, and CSU/CDU-related spam, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Total spam message volume by party

Figure 1: Total spam message volume by party

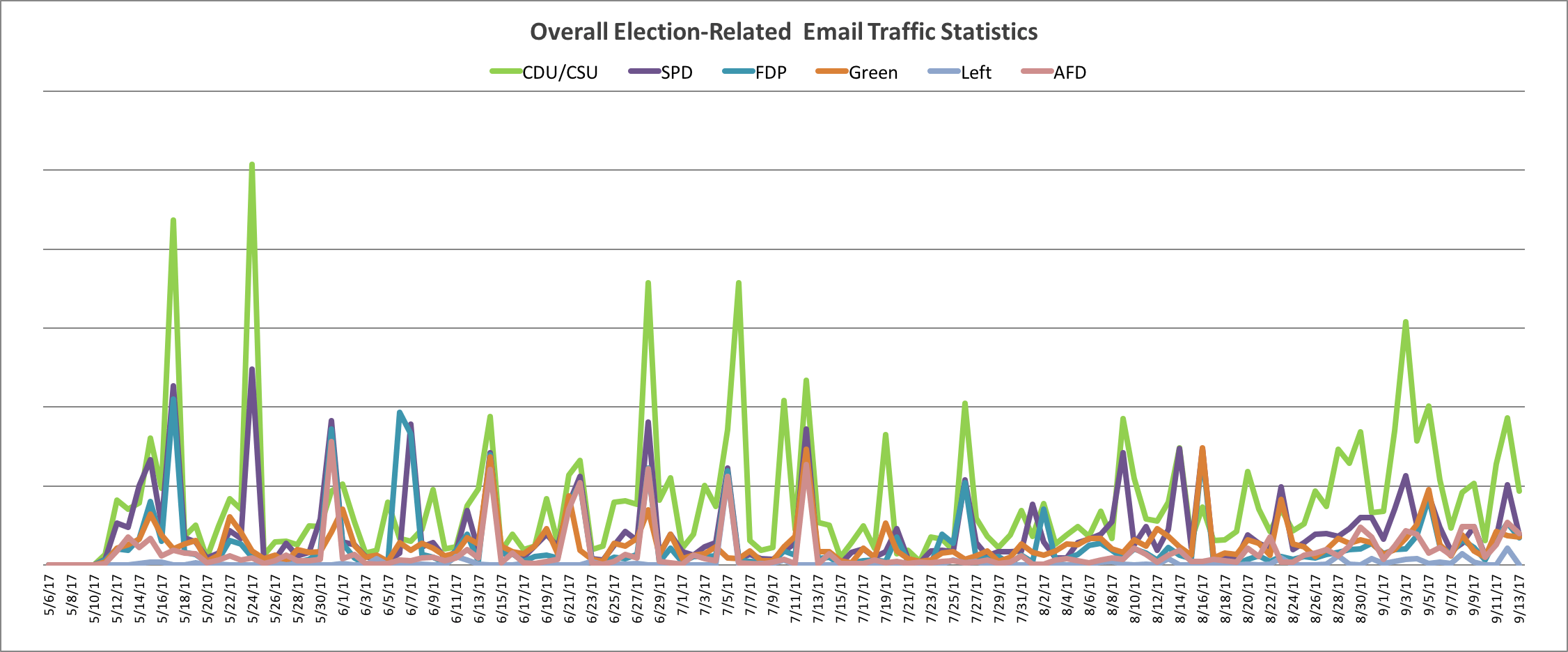

Individual parties and candidates often send legitimate bulk mail during election cycles. Figure 1 shows the combined “spam and ham” -- both unsolicited spam and party-sanctioned bulk mail -- associated with the parties and their national candidates based on the contents of subject lines. As in other elections we have examined, these combined volumes provide an indication of the overall noise in email for each party and tend to track well overall with volumes of only spam, albeit at much higher daily levels.

Figure 2: Overall traffic volumes with keywords related to German political parties

Figure 2: Overall traffic volumes with keywords related to German political parties

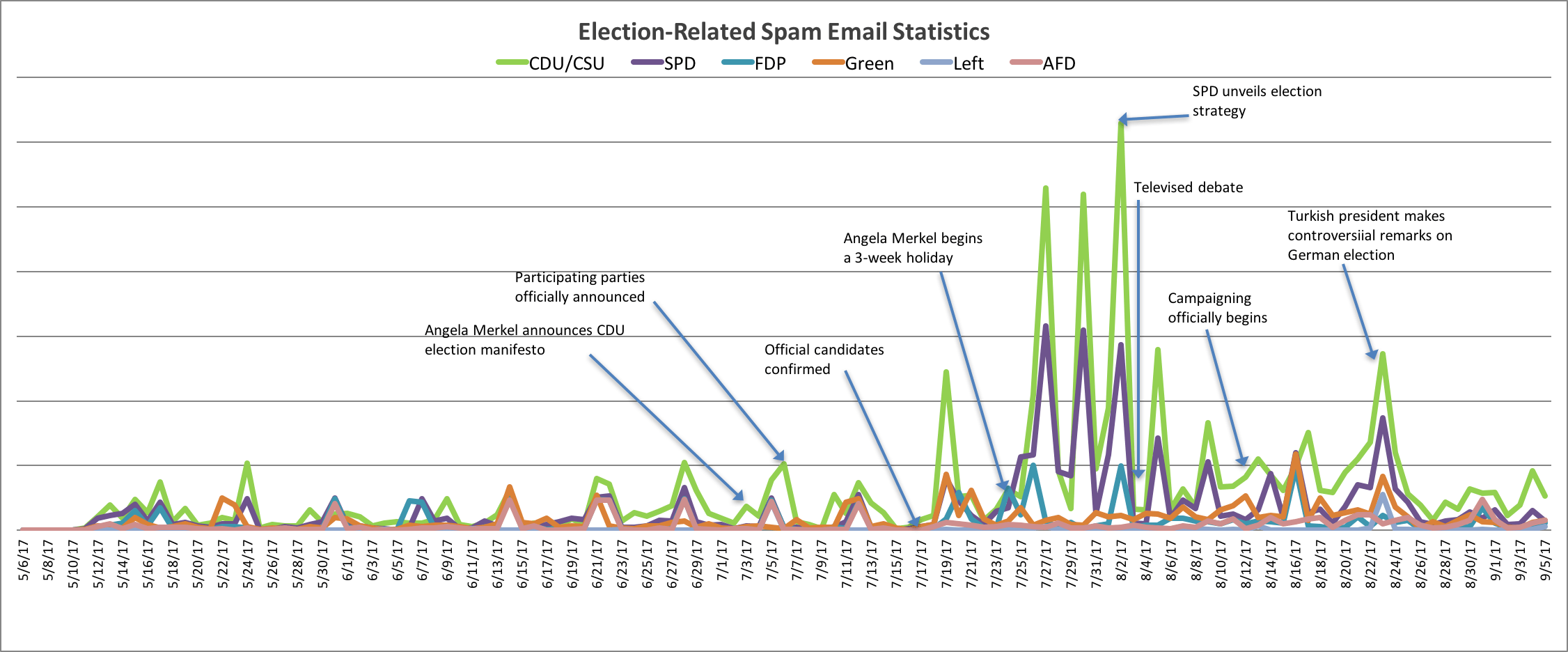

Figure 3 shows spam volumes only with parties and national candidates referenced in subject lines. Note that in both Figures 2 and 3, the CDU/CSU and SPD parties were associated with significantly higher message volumes than other parties. While legitimate mail drove large volume spikes both earlier in the election cycle and in the last weeks leading up to the election, spikes in July and August resulted primarily from spam.

These trends echo our observations in the US and French elections, where peaks in spam activity occurred two to three months prior to the election. Spam volumes then settled back into earlier patterns with occasional spikes, often associated with major election-related events or news that spam actors could leverage to develop more effective, timely lures.

Figure 3: Spam message volumes with keywords related to German political parties with key dates called out near spikes in spam volume

Figure 3: Spam message volumes with keywords related to German political parties with key dates called out near spikes in spam volume

Analysis of spam message subjects by candidates and parties typically reveals spikes in spam volumes associated with major or newsworthy events in the election cycle. For example:

- July 3: Angela Merkel announces the CDU election manifesto

- July 7: Parties declare their intent to participate (a small spike occurred the day before)

- July 17: Official candidates confirmed

- July 24: Angela Merkel takes a widely publicized holiday break

- August 1: SPD unveils election strategy

- August 8: Participating parties announced

- August 13: Campaigning officially begins

- August 23: Turkish president ignites controversy with statements about the German election

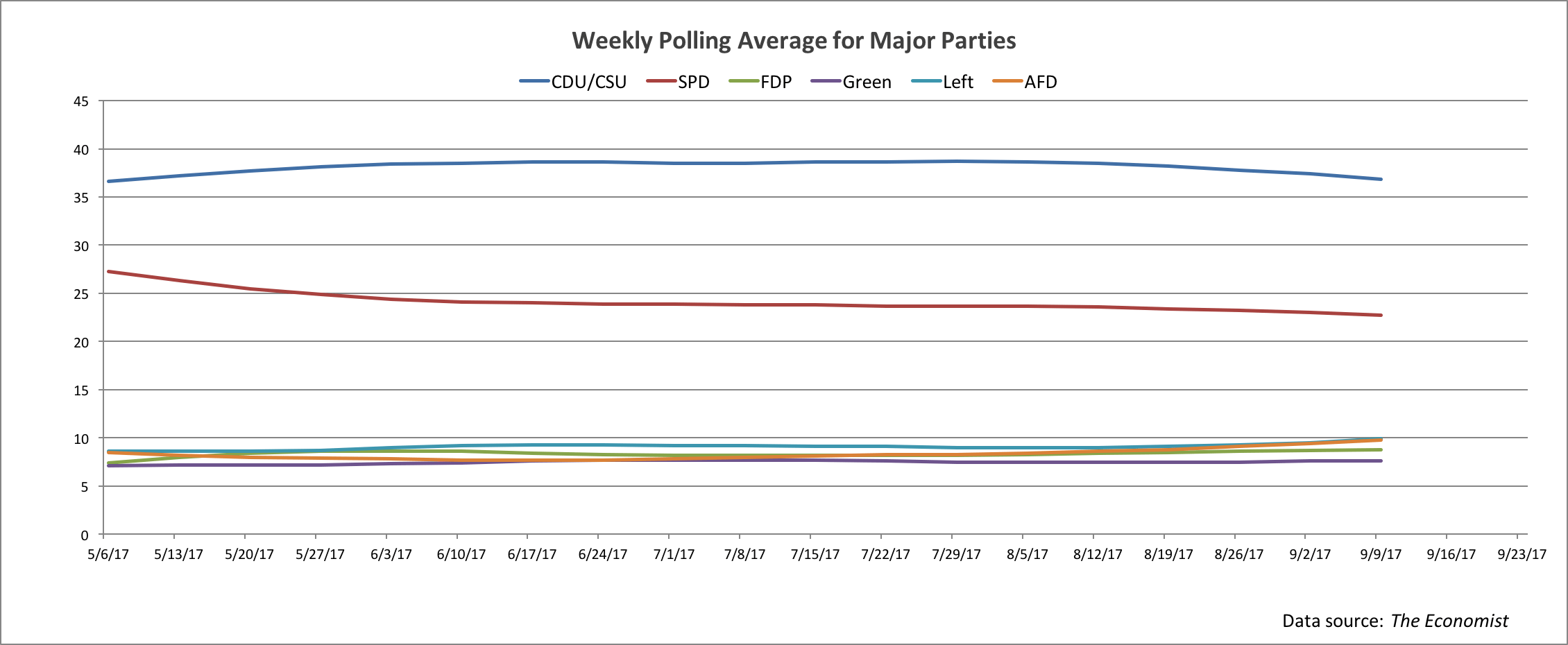

Opinion polls conducted over the course of the election cycle in Germany have demonstrated relatively steady positions for the national candidates and their parties (Fig. 4), particularly since early May, just before the North Rhine-Westphalia state election. Positions in the polls have been largely mirrored by consistent weekly spam message volumes and steady relative proportions of overall election-related spam by party (Figure 3).

Figure 4: Polling averages trend since May 2017. Source: The Economist

Figure 4: Polling averages trend since May 2017. Source: The Economist

Our analyses of previous elections found a correlation between spam subject message volume and brand strength, with spammers leveraging the more recognized and compelling brands to reach potential victims. In this regard, despite extensive speculation by pundits and politicians about the makeup of the post-election government, the clear surge in spam message volume related to the CDU/CSU and SPD in late July and early August suggest that before campaigning officially began, spammers had already made their conclusions that the election will result in the continuation of the “grand coalition” that currently presides in the Bundestag. While the popularity of Chancellor Merkel, the CDU/CSU, and the SPD has ebbed somewhat, spam message volume confirms that no other party can match their brand recognition and that in the end they will be forced to continue a partnership for which neither shows great enthusiasm. Moreover, spam subject preferences support polling averages for the other parties that reflect the absence of the populist groundswells that drove election results in the US and UK.

The spam messages associated with the election involve a wide range of topics, lures, styles, and destinations. Figure 5 shows a typical English-language lure with links to a news aggregator site. The site itself relies on affiliate marketing and advertising for revenue, making the sort of incendiary clickbait featured here especially attractive for spammers. While many such spam messages include links that are unrelated to the subject line, this particular example links directly to the site featured in the subject line.

Figure 5: Example spam leading to an English-language news site with affiliate advertising

Not surprisingly, much of the spam is in German, with links to German-language websites. However, as with the elections in the US, UK, and France, the German election has attracted significant international attention, providing material for spammers worldwide to increase click-through rates.

Conclusion

It is well-known that spammers combine strong brands with trending topics and events such as the Olympic Games, World Cup, and presidential elections to create spam email messages intended to convince people to open their emails and click through links to affiliate marketing pages, phishing sites, and more. Brand strength in this sense encompasses both positive and negative sentiment, and the stronger the brand, the more useful it is as a lure for spammers. While it remains to be seen how much influence – if any – spam email can have on the outcome of an election, recent elections in the United States, France, and the United Kingdom have repeatedly demonstrated the predictive power of spam volumes and the ability to use them as a barometer that is at least as effective as opinion polling in major elections. In the case of the upcoming German elections, it appears that spam actors have already cast their votes for the status quo.