Overview

Despite recent drops in values and ongoing volatility in the markets, cryptocurrencies remain the currencies of choice for threat actors and vast numbers of individuals attracted by the promise of both anonymous transactions and potential profits. For threat actors, the explosion of ransomware in 2016 and 2017, payments for which were largely made in bitcoins, provided infusions of cryptocurrency. Most underground markets also operate exclusively with cryptocurrencies, making them attractive targets. Recent high-profile breaches and thefts from major exchanges made headlines but many cybercriminals have now turned to coin mining malware, add-on modules for banking Trojans, and in-browser mining software to generate cryptocurrency revenue as ransomware has declined dramatically.

This blog describes the current state of coin mining malware, looks at historical trends driving malicious activity with cryptocurrency, and provides insights for organizations, individuals, and defenders, all of which are increasingly exposed to cryptocurrency-related threats.

Ransomware gives way to bankers and embedded mining capability

With the introduction of Locky in early 2016, an actor we track as TA505 introduced ransomware at massive scale in large global attacks. The large ransomware attacks from TA505 and others continued through much of 2016 and 2017, as did the rapid introduction of new ransomware strains. At the peak of their growth, multiple new strains were being introduced daily, the vast majority of which required payment in Bitcoin. For many consumers, this was a harsh introduction to cryptocurrency. Figure 1 shows a typical ransom message, complete with the “Bitcoin accepted here” logo.

Figure 1: Sample ransom message from Wana Decryptor 2.0

Figure 1 also illustrates a trend that we first reported in our Q4 2017 Threat Report: as Bitcoin values dropped and cryptocurrency markets became even more volatile, threat actors increasingly demanded payments denominated in local currency, even though those payments still needed to be made in bitcoins.

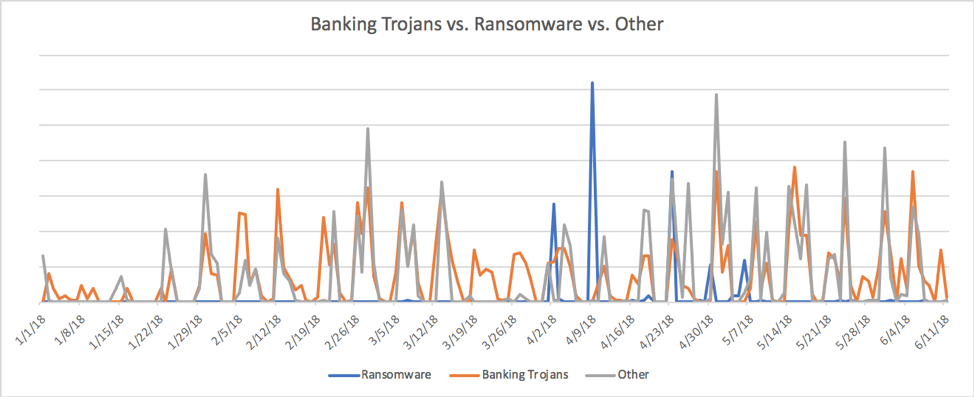

By 2018, however, ransomware payloads in email became far less common and were largely replaced with banking Trojans, information stealers, downloaders, and other malware. Figure 2 shows the relative mix of top malware categories in 2018, with ransomware falling far below message volumes associated with other malware families.

Figure 2: Indexed daily message volume of top malware categories, January-June 2018

The Trick banking Trojan drove much of this volume, with Zeus Panda (aka Panda Banker) and Emotet banking Trojan also appearing in frequent campaigns. A newer strain known as IcedID has also seen rapid adoption by several regular threat actors.

Banking Trojans - No longer just targeting bank accounts

Banking Trojans generally operate using webinjects that either modify or replace web pages from online banking sites to steal login credentials, conduct fraudulent transactions, and more. Most banking Trojan campaigns are regionally targeted as the webinjects must be configured for individual banks. However, many banking Trojan campaigns have added cryptocurrency mining modules or bots, known as “coin miners,” as later-stage payloads, expanding a trend that we first reported in Q3 2017. Other bankers—most notably, The Trick—added cryptocurrency mining modules to the primary payload.

At the same time, we have observed webinjects increasingly targeting cryptocurrency wallets and exchanges, as well as international online payment sites, making regional targeting less critical. For example, in March 2018, The Trick added the following cryptocurrency-related injects:

- Coinbase.com

- www.bitcoin.com

- Blockchain.info

- www.bitmex.com

- bittrex.com

- poloniex.com

- www.binance.com

- www.bitfinex.com

- www.bitstamp.net

- www.bithumb.com

- auth.hitbtc.com

- www.bitflyer.jp

- Zaif.jp

When Cryptocurrency Meets Commodity Malware

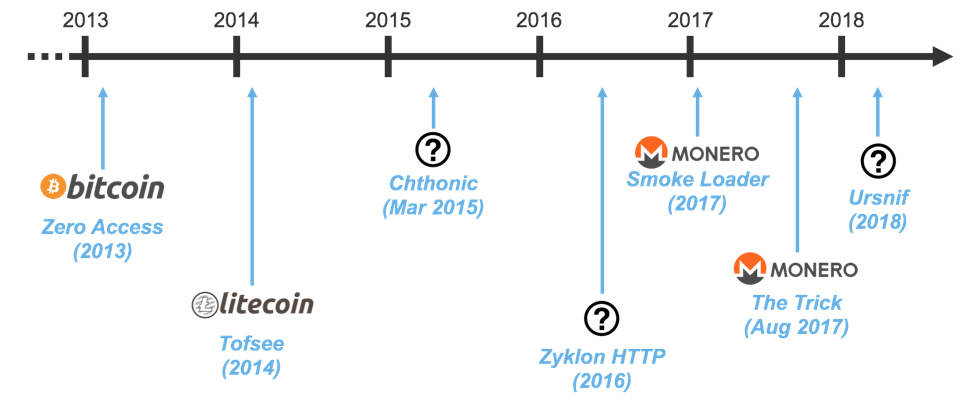

Figure 3: Timeline of introduction of mining modules to widely distributed malware; question marks indicate functionality requiring further research

Anatomy of a cryptocurrency miner attack

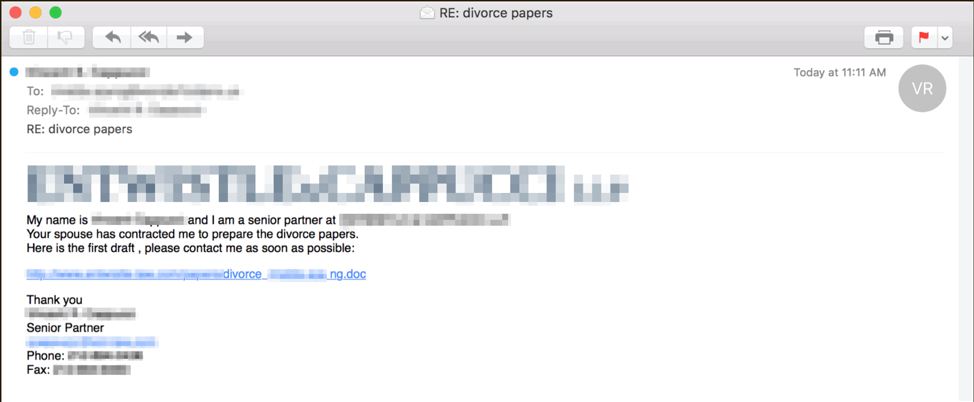

We have observed coin miners being installed via exploit kits (EKs), web-based social engineering schemes, and, most often, via email. One such email is pictured in Figure 4 and features a strong social engineering component to trick users into clicking the link and downloading the document.

Figure 4: Sample email lure spoofing a well-known law firm and using stolen branding with a linked Microsoft Word document that, when downloaded, contains macros that install coin mining malware

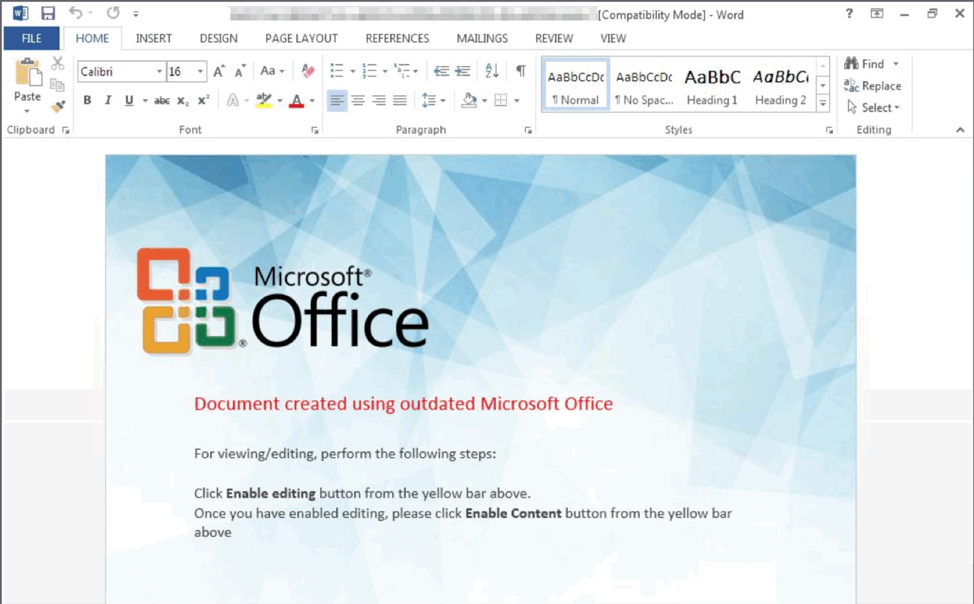

We regularly observe both linked and attached malicious documents, as well as PDFs, zipped scripts, and other malicious files, all designed to download coin miners, among other malware. Figure 5 was a sample document attachment from another campaign purporting to be a resume and, like many malicious documents, contains social engineering schemes to trick users into enabling macros, after which malware is downloaded and installed automatically.

Figure 5: Sample document attachment that uses malicious macros and Microsoft’s Background Intelligent Transfer Service (BITS) to download and install SmokeLoader; this in turn downloads a Monero coin miner

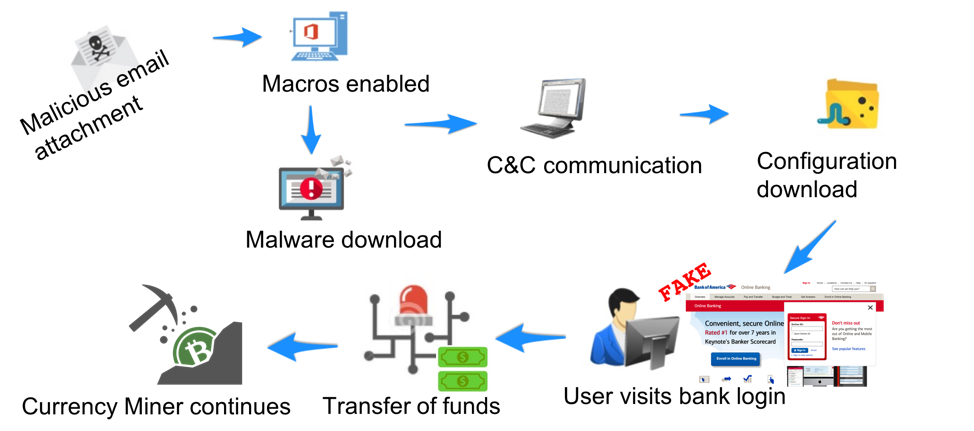

Figure 6 shows a typical attack chain beginning with a malicious document attachment. In this case, the downloaded malware is a banking Trojan that continuously mines for cryptocurrency even as attackers use it to steal credentials and conduct fraudulent transactions like a typical banker. Monero tends to be the cryptocurrency of choice for these types of miners as the currency can still be mined effectively with the combined desktop CPU resources of many infected machines. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is more commonly stolen directly as mining has become too processor intensive for anything but mining farms and high-performance computing clusters.

Figure 6: Typical attack chain using a malicious email attachment to deliver a banking Trojan with a coin mining module

It is worth noting that in some cases, attacks do not involve any malware at all. For example, we observed a threat actor creating fake cryptocurrency wallet sites and buying Google Ads to drive traffic to the sites. When users enter wallet credentials in the bogus sites, the group steals the credentials and can steal cryptocurrency funds directly.

Because nobody types those cryptocurrency wallet addresses

Cryptocurrency wallet addresses are long strings that are frequently cut and pasted by users. As a result, Proofpoint and other researchers have observed a number of targeted phishing emails that deliver malware that manipulates the clipboard, monitoring its contents for cryptocurrency wallets. The malware then changes copied addresses to hardcoded addresses owned by the attacker. Because of the length and complexity of the address string, it is unlikely that end users will notice the change and, instead of paying their intended recipient, deposit funds in the attacker’s wallet.

In one such campaign that leveraged previously undocumented malware, we verified this behavior for Bitcoin and found hardcoded addresses for Ethereum, Monero, and Liberty Reserve cryptocurrencies.

Coinhive - Busy as bees

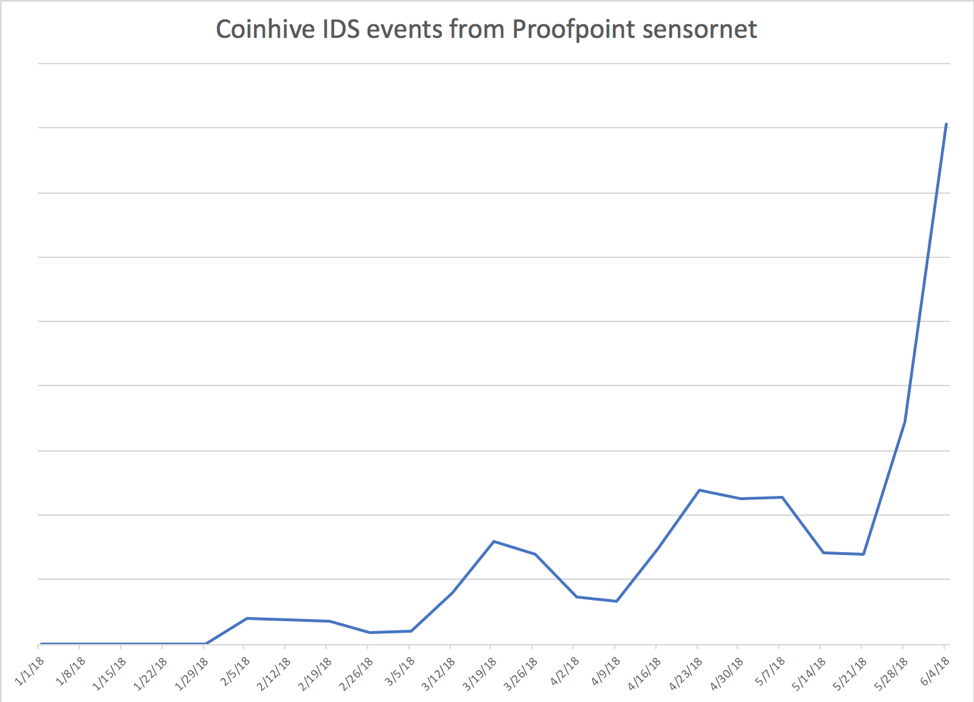

Coinhive was originally developed to allow website operators to monetize their sites by co-opting visitor CPUs to mine Monero cryptocurrency. Some sites have already implemented the JavaScript code, following the best practice of informing users of the activity and, in some cases, doing away with advertisements for a revenue stream. In many other cases, though, attackers have modified the code and inserted it on websites without informing users. Throughout Q2 2018, we have observed steady growth of events on our IDS sensor network relating to Coinhive and, beginning in late May, saw a rapid increase in Coinhive traffic, resulting in a 460% jump quarter over quarter (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Indexed coinhive events recorded on IDS sensors this year

We have also observed malicious use of Coinhive in the mobile space. For example, earlier this year, 19 Android applications, injected with the CoinHive JavaScript, were uploaded and made available through the official Google Play Store. The apps were secretly loading an instance of the malicious Coinhive script, which was executed whenever the user started the apps and they opened a WebView. When they were not using a WebView, the malicious apps hid the WebView component from view and ran the mining code in the background. These apps have since been removed from the Play Store.

Conclusion

Cryptocurrencies continue to make headlines, whether because of major thefts at cryptocurrency exchanges, allegations of currency manipulation, or market volatility. The real story, though, is often happening behind the scenes, as threat actors look to steal bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies directly from consumers with information stealers and banking Trojans configured to look for relevant credentials and software. At the same time, even as cryptocurrency values have fallen from the stratospheric levels they reached in 2017, threat actors continue to include coin mining modules and secondary coin miner payloads in the malware they distribute, creating new opportunities for monetization of email and web-based attacks.

For many actors, coin mining, whether through web-based cryptojacking or through installed malware, represents “free money”, regardless of currency volatility and is less disruptive than ransomware, dramatically extending the time window during which malware can persist on devices and actors can collect information and mine currencies.