Welcome to the second part of our blog series, which explores the value of incorporating nudge theory into security awareness training. In the first part of this series, we explored the fascinating concept of nudges and how they shape our everyday decisions without us realizing it.

Nudges are rooted in behavioral economics, gently guiding us toward desired choices. From the ATM that returns your debit card before dispensing cash to Google Chrome warning you about misspelled URLs, nudges play a significant role in influencing human behavior.

In our first blog, we also discussed the limitations of using nudges alone and introduced the concept of integrating nudge theory with learning science principles. Now, we’ll show you the transformative potential of combining theory with science by giving you some ways to effectively integrate nudges into your security awareness program. This can help you shape a strong security culture in your organization.

Designing effective nudges for security awareness

To create a robust security culture, businesses need to go beyond simply raising awareness and instead, foster a continuous learning and adaptive mindset. This is where the integration of nudge theory and learning science comes into play. By combining these two approaches, companies can shape a security-aware workforce that actively engages in risk mitigation.

We know that nudges have the potential to shape end users’ behavior in subtle but significant ways. However, we also know that nudges are not always effective in changing behavior, and their efficacy depends on a multitude of design factors.

To help overcome these potential limitations, we have argued that nudges should be combined with learning principles identified by behavioral research, such as cognitive science, to help mitigate against designing ineffective nudges. Toward that end, we have identified, and share below, four candidate examples from the cognitive and learning science literature that have proven to be effective in modifying learners’ knowledge and ultimately their behavior.

Tip 1: Connect the target material to the learner’s background knowledge

It’s almost impossible to remember a list of disconnected facts. But if you can weave them into a cohesive narrative that connects with what learners already know, then your target audience has a much better chance of remembering the contents of the lesson.

Ultimately, what we want to avoid is “inert knowledge,” where the facts that you learn about cybersecurity remain inaccessible. Instead, you want people to be able to apply what they know to their work and their personal lives.

To the extent possible, the content of a nudge should connect back to something that the learner already knows. If they don’t already have that background knowledge, then the nudge should lower the barrier for accessing that necessary information.

For example, Chrome will warn you if you navigate to a website that contains malware (see Figure 1). And as we know from the 2023 State of Phish report from Proofpoint, 69% of people know the definition of “malware.” So, this nudge is incredibly useful because it has a link defining what malware is.

Figure 1. Example of a browser warning that a site may contain malware.

Tip 2: Directly engage the learner with the target material

Watching a video does not ensure learning. Instead, the type and depth of cognitive processing determines if the student learns (or not).

People retain more information when they can be active participants in the learning process. Think about riding a bike. You can’t learn how to ride a bike by watching a how-to video on YouTube. Instead, you need to get on a bike and fall a few times until you figure it out.

The same is true for cybersecurity. To learn how to identify and report a phish, you need some conceptual information. Once you have that, you must then be put into the position of identifying a phish in real life because that is when you can identify gaps in your knowledge. It also helps to contextualize future conceptual training.

Tip 3: Repeat information to help learners with long-term retention

A nudge is typically a single shot in time. Unfortunately, not much information is retained when you see something once. Instead, three things need to happen to change behavior.

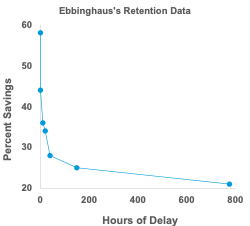

First, information needs to be repeated…often. According to advertising lore, an audience needs to be exposed to a marketing message seven times before they will remember and act on that information. While the rule of seven may or may not be true, there is an abundance of evidence for the power law of forgetting, which states that people only remember 44% of information after a delay of an hour, 34% after a day, and 25% after two weeks (see Figure 2). Seeing the same information spread out over time helps reduce the amount of forgetting.

Figure 2. The amount of information retained after various delay intervals.

Second, learning is optimized when the same information is shown in different contexts. The goal is to help the learner generalize their knowledge across multiple platforms. For example, what one learns about phishing also applies to guarding against smishing attacks. It’s a good idea to transmit the same message on various channels of communication (email vs. Slack/Teams vs. SMS) to assist in that generalization process.

Finally, seeing the exact same nudge over and over will result in losing people’s attention due to a cognitive process called habituation. Therefore, you need to vary the message, so it captures and holds your target audience’s attention.

One of the dangers of the Email Warning Tag (see Figure 3) is when users see it too frequently, they start to tune it out. That’s when it begins to lose its efficacy.

Figure 3. An Email Warning Tag (EWT) is a nudge that’s used in security awareness programs to reinforce behavioral change.

Tip 4: Give learners lots of feedback

We know from decades of research that learning is much more efficient when feedback is present. Otherwise, you are never sure if what you did was right or wrong—and that means you don’t know what should be repeated or what needs to stop.

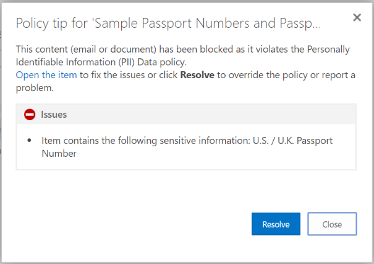

Nudges are sometimes used in response to specific behaviors. For example, if you try to send a file with Personally Identifiable Information (PII), the end user might get a nudge in the form of a warning (see Figure 4). That is feedback. So, the next time this person attempts to share sensitive information, they hopefully will remember the warning and reconsider their actions.

Figure 4. This pop-up warns the user that a document someone is attempting to share contains PII. It counts as a nudge example (and not policy enforcement) because it does not prevent the action.

Risks to watch out for

While nudges can be powerful tools in shaping user behavior, it’s important to be aware of potential risks. Take these risks into consideration when designing your program using nudge theory:

- Overreliance on nudges. Relying solely on nudges may lead to complacency or a false sense of security. Be sure to strike a balance and not overlook other aspects of security awareness training that should be emphasized, such as providing comprehensive knowledge, building critical-thinking skills and promoting a proactive mindset. Nudges should be seen as a complementary component of a holistic security awareness program.

- Nudge fatigue. Repetitive or intrusive nudges can lead to nudge fatigue, where individuals become desensitized or resistant to their influence. To prevent this, make sure that nudges are diverse, contextually relevant and delivered in a balanced manner. Regularly evaluate the impact of nudges and adjust their frequency and content accordingly. And provide options for learners to control the delivery of nudges, allowing them to adjust preferences based on their individual needs and preferences.

A powerful tool to help users become better defenders

In this two-part blog series, we have explored the power of nudge theory in shaping behavior and enhancing security awareness. By combining nudge theory with behavioral science, companies can transform their security culture, foster continuous learning and reinforce positive security habits.

Effective nudges—designed with background knowledge, learning by doing, distributed learning and feedback—can have a significant, positive impact on security awareness outcomes. However, it’s important to strike a balance and avoid overreliance on nudges, and to be mindful of potential risks such as nudge fatigue.

By harnessing the power of nudges and adaptive learning, businesses can unlock the full potential of their security awareness programs and empower individuals to be the first line of defense against cybersecurity threats. Let’s nudge minds and enhance defenses together.

Learn more

To delve further into the nudge theory approach and explore more examples, we encourage you to download Nudging Our Way to Safer Cybersecurity Habits. This white paper offers a comprehensive exploration of nudge theory, adaptive behavioral learning and practical guidance on how to use these concepts to improve security awareness.